Patek Philippe 5004A(cier)

A Historical, Technical, and Aesthetic Look – June 2023

Many friends, enthusiasts often inquire whether my interest in watchmaking extends beyond A. Lange & Söhne—a question that has always intrigued me. The world of watchmaking is a vast tapestry, encompassing more than just one brand or country. While my deep admiration lies with A. Lange & Söhne, it is crucial to acknowledge the broader landscape shaped by years of exploration, study, and the appreciation of numerous watch brands.

The allure is not confined solely to the products themselves but rather the rich history, compelling stories, and the remarkable individuals who have left their indelible marks. Today, I embark on a new journey—one that opens the doors of Langepedia to other brands, watches I admire. Starting with a personal favorite: Patek Philippe. Let me rephrase: Starting with a favorite friend’s (@watchcandies is his name) Patek Philippe 5004A, a mesmerizing Split Seconds Chronograph crafted in steel.

While writing this article, I sought help of a one particular friend also: Many of you would know him by the moniker of @happy60mins on Instagram. A man with impeccable style, taste and invaluable friendship. Through his photos, his brilliant perspective on design and details, we are set to explore the history of Patek Philippe’s development of perpetual calendars, split seconds chronographs, and of course possibly the most magnificent watch lineage ever created, Patek Philippe’s Perpetual Calendar Chronographs, with particular emphasis on design, technicality, and why they matter at all.

As a primer, let us touch on how each complication came to be in the world of Patek Philippe, while also exploring the movements.

Please, enjoy

Patek Philippe - Historic King of Watchmaking

Those are not our words, but Günter Blümlein’s from the interview he conducted with Peter Chong in 1999, just before the launch of the Datograph at BaselWorld. Perhaps he used the word ‘historic’ in anticipation of the launch of the first in-house chronograph introduced since decades? I’m not certain. What we do know is that we agree! But why? What makes Patek Philippe, particularly their chronographs and perpetual calendars so admirable and collectible? To understand that, we must journey back several lifetimes.

The Patek Philippe Chronograph

Patek Philippe’s history with chronographs dates back to 1856. The brand would acquire movement blanks from specialists, complete the finishing touches in-house, and offer them for sale. Over time, the complexity, architectural design, and craftsmanship of their chronographs reached levels that remain awe-inspiring even today. Behind these extraordinary creations, there was one special manufacture that us enthusiasts hold in high regard: Victorin Piguet.

According to Collectability of John Reardon, the Piguet Family’s initial interaction with Patek Philippe can be traced back to the 1840s with the introduction of minute repeater pocket watches. However, it was in the 1880s when their relationship truly flourished, as the Piguet Family excelled in producing split-seconds chronographs. For many years, Patek Philippe relied on the exceptional ebauchés crafted by Victorin Piguet, whether for pure chronographs or grand complications featuring calendars and repeaters-in my opinion, those pocket watches are some of the best bargains today. It was through this partnership that the world’s first rattrapante wristwatch was unveiled in 1923.

The first wristwatch split-seconds chronograph. By Patek Philippe in 1923, ebauché from Victorin Piguet. Delicious. Sold at Sotheby’s.

Following that, in 1924, Patek Philippe introduced its first wristwatch chronograph. It featured a remarkable Piguet ebauché, an officer back, and Breguet numerals. Then, in 1925, Patek Philippe unveiled the world’s first wristwatch Perpetual Calendar. Interestingly, the movement for this watch was crafted back in the 19th century but remained unsold until its introduction as a wristwatch.

From that point onwards, Patek Philippe embarked on a journey of exploration, experimenting with different chronograph designs and complications across various references such as the 130, 530, 533, 1463, and 1579… Each reference, in our opinion, surpasses the other in terms of beauty, significance, experimentation, characteristics and romanticism. However, during this era, against multiple basic chronographs, Patek Philippe only produced two Split Second Chronograph references: 1436 and 1563. Aaand done.

Various designs of Patek Philippe Rattrapantes from the 20th century. Courtesy of Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Antiquorum Watches.

From the reference 1563 of Duke Ellington which now resides in Patek Philippe Museum, to the unique single-button split-seconds chronograph (far right on the picture above) made for William Boeing, Patek Philippe’s Chronographs, be it the basic or rattrapantes, graced wrists of the most famous artists, industrialists. Deservedly so. To this day, with the clarity of design, be it the dial or the case, extreme attention to detail and the impeccable finish all around, Patek Philippe’s vintage indeed showcases why Blümlein calls the brand as historic king of watchmaking.

Yet, for decades, we haven’t seen a pure chronograph from Patek Philippe, let alone a rattrapante. Because, the spotlight shifted to what is arguably the most magnificent watch lineage ever created: Patek Philippe Perpetual Calendar Chronographs. Before movingonto there, let’s look at the other half of the story.

The Patek Philippe Perpetual

To prefix one name on a complication might sound a little haughty, but if there’s any maker deserving of such praise, it would be Patek.

Patek Philippe’s history with perpetual calendars goes back to 1860s, and with a rather classic approach. You know the one; four individual apertures with plenty of space on the dial, and at times often coupled with the wet dream complication of a watch enthusiast, the minute repeater or the Sonnerie. In time, PP crafted incredible well done pocket watches, mainly with the ebauchés provided by Victorin Piguet (more on that in the chronograph section), examples include the one of the earliest Grand Complications by the brand in 1890s, or all the way to Henry Graves Super Complication.

It was in 1925, Patek Philippe introduced the world’s first wristwatch perpetual calendar, following the classic design cues of its time.

From then on, the perpetual was a seldom occasion at Patek Philippe, crafted mainly for the pocket watches. The year was 1941, and the reference number is 1526, Patek created their first serially produced perpetual calendar wristwatch. You must understand that Quantième Perpétuel isn’t unique to Patek. Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet and many others also had their own interpretation, but this information was mainly presented in 4 sub-dials.

With ref.1526, Patek basically took this complication and made it theirs with the now iconic twin apertures of Day/Month above their signature at 12. These ‘windows’ plus running the dates along the circumference of moonphase indicator at 6 was an ingenious design move back then, and what we now say is quintessentially Patek Philippe, elegance par none.

Patek Philippe 1526, from Christie’s Auction in 2017.

To this very day, I (Alp) still find myself gazing at this perpetual calendar layout and pondering whether there exists a more enchanting, optimal, legible and logical arrangement than this one. Oh, the perpetual quest for perfection! Countless attempts have been made, each one daring to take a different leap into the intricate depths of this centuries-old complication. Yet, in my humble opinion, none can hold a candle to the audacious brilliance that Patek Philippe achieved right out of the gate.

Now, let’s turn our mischievous eyes to A. Lange & Söhne, for the website name demands such mischief. The Saxons dared to break free from the shackles of convention, departing from the traditional Swiss perpetual calendar layout, Patek Philippe included. With a bold proclamation, Lange placed the signature big date front and center, proudly proclaiming its supremacy as the most vital indication of a perpetual calendar layout. Oh, but there’s a catch! As complexity grows, so does the challenge of legibility, as witnessed in their sensual creation, the Datograph Perpetual.

To test Alp’s theory, what is the first thing you notice on my Datograph Perpetual below?

The 410.038. Courtesy of our co-author @happy60mins

Indeed, positioning it front and center worked as advertised. The big date, as inspired by the Semper Opera House is a key design element of Lange 1, dating back (pun intended) to 1994, when the very first Lange 1 was born. As much as I’m tempted to go on about the superb Calibre L952.1, it is beyond the scope of this article. But if you really wanted to know more, click on this link: Datograph Perpetıal. This Langepedia guy seems to know a thing or two about Lange. Mischief managed, and back to Patek’s PCC.

A Patek Philippe Dynasty - PerPetual Chronograph

From the first to utilize split-seconds chronograph and perpetual calendar complication in a wristwatch, you can expect one thing: To merge both!

While very innovative with its clean display, some might say ref. 1526 is plain in design. Its lack of popularity might also have something to do with the fact that in the same year, Patek launched the most seminal ref. 1518.

To fit a grand complication like perpetual calendar and a chronograph function in a petite 35mm calatrava-esque case is nothing short of magical, except it wasn’t “abracadabra” that Charles Stern (President of Patek then) said. I think he might already have the idea of making this double complication. Otherwise, why would ref. 1526 have two empty spaces at 3 and 9, as if begging to have two sub-dials drawn in.

This is also why I postulate that Patek redirected most of their chronograph production into developing the PCC line, resulting in the aforementioned hiatus of manual-wound chronographs. Putting aside my conjectures, what is indubitable is that ref. 1518 paved the way for future PCC. For the sake of brevity (the irony), I will focus on the PCC immediately before (ref. 2499) drawing comparisons for a better appreciation on how ref. 3970, i.e. the non-rattrapante of ref. 5004 evolved to.

Patek Philippe’s lineage of Perpetual Calendar Chronographs until the introduction of 5004

When discussing Patek’s Perpetual Calendar Chronograph (PCC), the word ‘lineage’ as Alp aptly mentioned is key. To me, each reference is never a stand-alone model, but a distinct species along an evolutionary branch, akin to Darwin’s Tree of Life. Every reference reflects not just the taste of the times but of the leadership as well. Much like the theory of evolution, you will see clear hereditary traits as the PCC evolves aesthetically and technologically, which are also the two prongs of my approach moving forward.

As a descendant of the first serially produced PCC ref. 1518 (circa 1941), ref. 2499 had big shoes to fill and it did more than just that. Produced from 1950 to 1985, ref. 2499 reified Patek’s position as one of the most desirable PCC to own. In my opinion, its longer production period (35 years) straddled a fine balance between access and rarity. It caught many eyeballs across a whole generation, while its small production of around 9 pieces/year ensured a certain exclusivity.

With a slightly larger case size of 37.5mm (ref.1518 – 35mm), it is very much suited for the modern taste today, and probably considered ‘Jumbo’ back in the day. To be more exact, earliest cases made by Vichet were slightly smaller, at 36.2mm with a flat caseback. Later series made by Wenger were larger, at 37.5mm with a more domed profile.

Thanks to Sotheby’s and Christie’s Watches Departments for brilliant imagery

Before delving into the minutiae, let us zoom out a little. Remember I mentioned that the watches were not just a reflection of the times, but also leadership? While their timepieces were constantly evolving, so did its leadership. In 1977, Mr Henri Stern handed over the reins to his son, and the current Honorary President of Patek – Philippe Stern. With that crown, came the responsibility of designing the next PCC – ref. 3970.

3970s cases are made by the same supplier – Ateliers Réunis – at a smaller and consistent size of 36.2mm. They have familiar pump pushers from ref. 2499 as well. The most important change was perhaps from Second series onwards, where cases are waterproof thanks to a screwdown caseback and stated so with an appended E = étanche, or waterproof.

The dial had a few changes transiting from ref. 2499 to 3970. The first, and perhaps most obvious is addition of leap year and day/night indicators inside the subdials. I guess Patek finally decided to acknowledge those born on the day of 29 February. From Third series onwards, the leaf hands are swapped with straight baton hands, while indices now come with a triangular tip, making them more prism. I must make special mention of my favourite detail here: pyramidical indices at 3, 5, 7 and 9. To my eyes, these and rounded dot indices are one of the most elegant way to declutter the dial. In sum, ref. 3970 saw further minimising of flourishes, favouring much cleaner aesthetics.

3970 (left) and 5004 (right). Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Big changes are also present on the back, with a similar path.

Piguet - Valjoux - Lemania

Alas, I am very well aware how boring this section is going to be following H60M’s illustrative introduction and dissection of Patek Philippe’s brilliant design language and its subsequent evolution, I wanted to have a look at these watches from behind (no pun). In the end, it is a chronograph, how can I not?

Before moving onto the impeccable 5004, we just want to deliver the evolution of Patek Philippe’s chronographs, so that we better grasp the generations, as well as the brand’s tradition of outsourced movements and how they were modified to exacting standards of Patek Philippe.

As highlighted in the introduction, the profound influence of Victorin Piguet is evident in a considerable array of intricate Patek Philippe pocket and wristwatches from the 19th and 20th centuries. Patek Philippe would entrust the task of crafting movements to the skilled hands of Piguet, who would meticulously refine them to perfection before they were delicately encased. I wholeheartedly encourage you to explore not only the Piguet movements found within Patek Philippe timepieces but also those incorporated into the creations of other esteemed watchmakers. As H60M astutely observed, the hallmark of true leadership radiates with resplendent brilliance.

Patek Philippe Single Button Chronograph from 1924, with an incredibly well finished Victorin Piguet inside. Courtesy of Antiquorum, auctioned in 1991

Patek Philippe’s introduction of the first wristwatch chronograph in 1923, followed by subsequent releases in 1924, was no mere coincidence. The demand for chronograph wristwatches soared in the aftermath of World War I. Patek Philippe, with its rich history and strong ties to Victorin Piguet, as well as its expertise in assembly and finishing, naturally emerged as a frontrunner in this field. However, the surging demand presented challenges due to Piguet’s meticulous artisanal approach, resulting in production delays and increased costs.

A significant turning point occurred in 1932 when the Stern brothers invested in Patek Philippe, setting the stage for remarkable developments. Recognizing the immense potential of chronographs, Patek Philippe introduced the iconic reference 130 in 1934, serving as a timeless canvas for future innovations.

The long quest for a suitable chronograph movement finally reached its conclusion in 1939. The Stern brothers, along with Jean Pfister, the technical director at the time, discovered the renowned Valjoux SA’s 23VZ. With its dimensions of 28 x 5.85 mm, it was the perfect fit for the 33 mm reference 130 and the models that would follow. Patek Philippe introduced its first chronograph with Valjoux in 1939, marking the end of the era dominated by Victorin Piguet.

Patek Philippe 2499 with Valjoux beating inside. Brilliant craft. Courtesy of Christie’s Watches

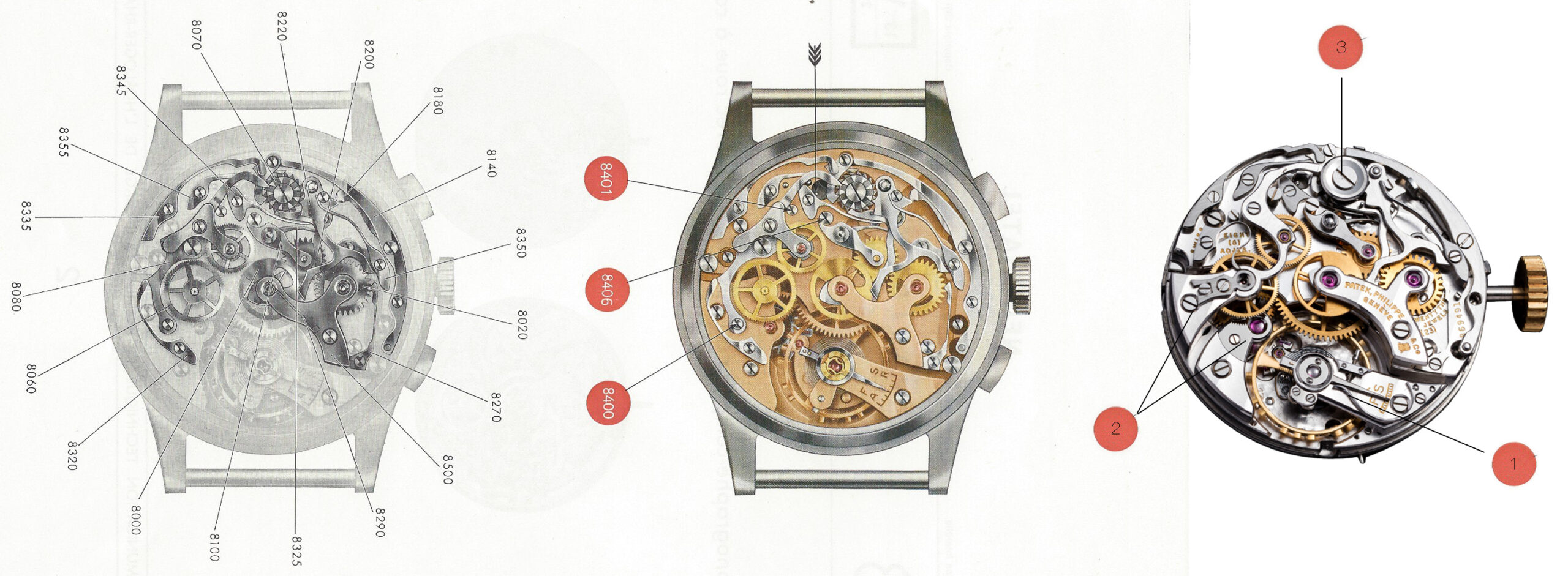

Valjoux 23, and its evolution to become a Patek Philippe. Diagram source: Ebauchés SA

When examining Patek Philippe’s rendition of the Valjoux 23, one cannot help but admire the exceptional finishing work. The presence of inward angles, a flat polished escape wheel cock, and a cap on the column wheel exemplify the meticulous attention to detail. Additionally, the brush finish on the chronograph levers and the polished screw slots further enhance the overall aesthetic. However, it is the three notable technical and architectural changes that truly captivate:

- The inclusion of a swan’s neck regulator.

- The separation of the escape wheel and driving wheel cocks under individual bridges, while the rest of the train is connected by a delicately curved bridge.

- The addition of a cap on the column wheel, a feature traditionally used in pocket watches to prevent any jumping or movement of the wheel.

Comparing Patek Philippe’s implementation of the Valjoux 23 with that of other manufacturers, the distinction becomes as vivid as Gandalf’s return in “The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.” It becomes evident why timepieces from Patek Philippe’s vintage era hold immense value, and why collectors worldwide passionately seek out these pieces, surpassing the allure of the brand’s current lineup.

Sadly, the Valjoux manufacturer fell victim to the quartz crisis and the rise of self-winding chronographs. In 1974, production of the caliber 23 came to a halt. However, ever resourceful, Patek Philippe had already amassed a reserve of these movements, ensuring the continued production of the exquisite reference 2499 until 1985. As H60M likes to illustrate, this is merely a stepping stone in the evolutionary chart. Out of the dust of Valjoux, Patek Philippe embraced and gave birth to another legend: the Lemania 2310/CH 27-70 inside the iconic reference 3970.

A Patek Philippe 3970 on bracelet with Lemania Movement. Courtesy of Sotheby’s

The modifications carried out on the Lemania 2310 to transform it into the caliber CH 27-70 are extensive. According to Patek Philippe, over half of the provided components underwent modification or replacement. The agreement stipulated that Lemania would supply the fundamental gear train and components, while Patek Philippe would take charge of the rest. In a letter dated 2010, the brand describes the modifications as follows:

“For functionality and traditional reasons, the escape-wheel and fourth-wheel cocks, the chronograph bridge, as well as the configuration of the clutch lever were redesigned along the lines of the 1923 role model, the first wrist chronograph. Tooth profile and transmission ratio changes allowed the torque curve to be optimized and boosted the caliber’s power reserve by 20% to 60 hours. Of course, the heart of the new movement is the Gyromax balance invented and patented by Patek Philippe as well as a hairspring with a Phillips overcoil”

Omega’s (left) and Patek Philippe’s (right) interpretation of the same movement

In 1994, for 54 years, Patek Philippe’s flagship has been its perpetual calendar chronographs. The Genevan delivered year after year, series after series, with slight touches on design with the changing times, offering immense collectability across all references and variants. As H60M touched upon, the focus on refining and perfecting the flagship. Yet, the market was booming in the ’80s and ’90s, and Patek Philippe was once again the forerunner, as demonstrated by the Antiquorum’s thematic auction in 1989. It was time that Patek Philippe would offer something more than a perpetual calendar chronograph (on the chronograph front) and in 1994, a year after Philippe Stern took the helm, we were greeted by the irresistable Patek Philippe 5004. A split-seconds chronograph from the Genevan after decades, merged with the iconic perpetual calendar layout.

Patek Philippe 5004

Thanks to the deluge of information above, we are cognizant that the Perpetual Calendar Chronograph (PCC) double complication is the unofficial flagship of Patek Philippe.

Before diving into the elusive ace that is 5004Acier, let us have a look at the entire production of this reference.

Here are some simple (official) numbers to set the tone:

-only 12 pieces made per year

-produced from 1994 to 2012 = 216 x ref. 5004 across a range of metals from Rose, Yellow, White Gold, Titanium (unique piece for Only Watch) and Platinum.

-a final run of rumoured 50 x 5004(A) in stainless steel was produced.

NOTE: As an interesting aside, according to some industry experts and long-time collectors, these official numbers from Patek Philippe literature and many online publications are severly under-estimated. Especially, the production on the precious metal side seems to be way above 12 pieces a year claim, where we are talking about mid to high hundreds. Again, on steel, numbers seem to be on the high two digits, and a bit. @charlestearle‘s post on the matter is a good brief.

The Divine Case & Dial

While the dial colour and metal varies across the range of 5004, few things remain the same. Double-stepped bezel and case, arabic numerals, cabochon (dot) indices for the other hours. These might all seem like facts, but thanks to the above information, you can probably spot certain familiar traits. If you don’t, shame on you. Jokes aside, you will see that the arabic numerals are very much inspired by the OG ref. 1518, while the pump pushers are from ref. 2499 (except first series).

In what I think is a bid to ‘play God’, à la gene editing/selection, Patek basically cherry-picked the best aesthetic traits from each prior PCC and assembled it all into this ref. 5004. Think Brad Pitt’s face, Chris Evan’s Body and the charisma of George Clooney. Although if I had it my way, I’ll throw in a tachymeter but that’s a story for another day.

From afar and looking at the dial alone (pic above), it is almost impossible to differentiate between this 5004A and its non-rattrapante variant – ref. 3970. Without seeing an extra pusher on the crown, this is the ultimate #IYKYK watch. And if you don’t know what that acronym means, then you are the living proof of this point. I jest. To me, this seeming act of mischief is a reflection of its creator – Philippe Stern – that stays true to the essence of Patek’s philosophy, one that is epitomised in his wearing of ref. 3940, a very unassuming automatic perpetual calendar.

The 5004A boasts a diameter of 36.5 mm and a thickness of 15 mm, displaying a substantial wrist presence. However, Patek Philippe has ingeniously transformed this mass into a work of art.

Patek Philippe 3970 (left) and 5004(right). Courtesy of Sotheby’s

The 5004A’s concave bezel in the 3970 has been transformed into a convex shape to accommodate the increased thickness and provide more space for the bezel. As a result, this creates a slimmer profile and highlights Patek Philippe’s commitment to crafting perfect cases with delightful curves and intricate details. Take a closer look at the bezel, with its added step, and notice the same attention to detail on the bottom with its diminishing structure.

Put yourself in Mr Stern’s head for a moment and think: “If we are making an end-of-series celebration for this extremely amped-up model of PCC, which metal should we encase it in?” Well, the plebeian steel, of course. You can only imagine the baffled faces on all his executives, perhaps the same look many art critics gave when they first saw ‘The Starry Night’ by Van Gogh. There is a certain craziness in the strokes, but as it turns out this stroke of housing ref. 5004 in stainless steel is one of genius.

A luxurious watch from a luxury brand ought to be cased in precious metal. This ref. 5004 has seen every iteration of preciousness from white, yellow, rose gold and even the apex of them all – Platinum. Lest we forget, Philippe Stern is, as we remember from his ref. 3940, someone who prefers his watches to be more understated, although no less complicated. In line with that and what I think is a brilliant yet counter-intuitive marketing move, he chose an utilitarian metal that is stainless steel.

Some might point out that ref.5004A isn’t the first Patek dress watch to be cased in stainless steel, and you’re right. Here, I must make special mention of Mr John Goldberger and his authoritative book “Patek Philippe Steel Watches”. See the below image and try to spot the most complicated timepiece of them all – clue: it is this 5004A.

The book of John Goldberger’s Bible of Patek Philippe Steel Watches. Source: Johngoldbergerwatches.com

From this comprehensive guide alone, there are 187 models including those in current production in stainless steel. Point is, for a man such as Auro Montanari (Goldberger’s real name) to spend time and effort documenting one type of metal for Patek watches, you can probably deduce that it is rare. Yet, does being rare make the 5004A more desirable?

Actually, it does. Based on the latest auction results from Phillips and at the time of this article (May 2023), a 5004A will cost you CHF 939,800. Say you’re one of those who doesn’t care about secondary market prices, here’s my own take. Given that steel is more resistant to corrosion and oxidation than precious metal, it makes this 5004A more appropriate to wear on a daily-basis, and isn’t the point of buying watches so that we can wear them…? As to whether one might wear a million bucks on their wrist as a daily is purely down to choice and obviously means. Personally speaking, this is why I love Vacheron’s Cornes de Vache in stainless steel, which also features the same Lemania-based chronograph/Cal.1142, a perfect blend of modern interpretation and traditional watchmaking. And on this timely note, let us dive into the movement.

Patek Philippe 5004 Movement

Those of you with an astute eye would realise that the base calibre of ref. 3970, the non-rattrapante brethren is called CH27-70 Q, and featured within this petite 36.7mm case is a movement with an additional letter ‘R’ – Rattrapante.

The best way I can describe this movement is likening it to a famous boxer. We all know of this famous quote – He floats like a butterfly, stings like a bee – used to describe the late legend that is Muhammed Ali. This CHR 27-70Q is slightly different. It is potent, petite and it weighs like a feather. Entering the ring is Featherweight Boxing King, Manny Pacquiao. Coincidentally, housing this powerhouse of a movement is the 36.7mm case in stainless steel, making this the lightest 5004 of them all, (except the Titanium 5004 for Only Watch Auction in 2013).

At 1.91m tall, Ali is a towering figure of fear. Compared to that, Pacquiao measuring at only 1.66m may not seem intimidating at all. The real fight only begins when you see this nifty little isolator-mechanism in action. Coincidentally, it is shaped like an ‘Octopus-wheel’, which is probably what it feels like fighting Manny Pacquiao in the boxing ring: an opponent who has 6 more arms than you: punches flying into your face from all over, while your two meagre humanly arms can barely block. As such, I need to tag myself out and let my partner-in-arms – Alp – take on the real technical details of this little beast.

Life is like a beautifully intricate chronograph movement, where each component is meticulously crafted and delicately synchronized. Just as the chronograph embodies the essence of timekeeping, life is driven by our desire to unravel the mysteries of existence. I know… This statement is perhaps as vague metaphor as Forrest Gump’s life is like a box of chocolates. However, unlike Forrest, the captivating movement of the Patek Philippe 5004 has me entranced, and I’m determined to explain its workings to you, as if finding my way out of a jungle.

Before we dive deep into the split-seconds chronograph version of the Lemania 2310, first, we must understand how a basic chronograph works. In the below diagram, I tried to label important parts, as well as put a visual comparison between the basic and the rattrapante chronograph.

Patek Philippe’s 3970 with Lemania (left) and the 5004 with the added spice of rattrapante gear highlighted (right). Base images: Sotheby’s

The processor of this caliber is the column-wheel. It is the link between the pushers and the function we see. If you look closer, you are going to see that the clutch lever (the lever carrying running seconds and intermediate wheel), zero-reset lever and the operating lever are all connected to it. The chronograph becomes active when the operating parts of the mechanism connects to the running movement. When the user presses the start button, column wheel spins forward and pushes the clutch lever’s tail in between the pillars. With this motion, the clutch lever moves horizontally (thus the horizontal clutch) and meshes with the chronograph wheel. To stop, pressing the button again, the clutch lever sits on the pillar again and disengages from the chronograph mechanism.

The reset mechanism works in a similar fashion. Upon pressing, the reset lever interacts with the heart shaped cam that sits on top of the chronograph seconds (as well as the minute counter) wheel. With the engagement, the heart shaped cam snaps to its starting position, moving the chronograph seconds’ wheel with it-thus completes the cycle.

Albeit relatively simple in explanation, construction of a chronograph movement is an extremely delicate and a genius-demanding task. As the chronograph is simply like a fungus, draining energy from the mainspring, arranging the tolerances, the energy flow and the seamless interaction between the levers and wheels requires great dexterity. Split-seconds chronographs however, carries this to the next level.

The following excerpt is from Patek Philippe, and who better to present it than the creators themselves?

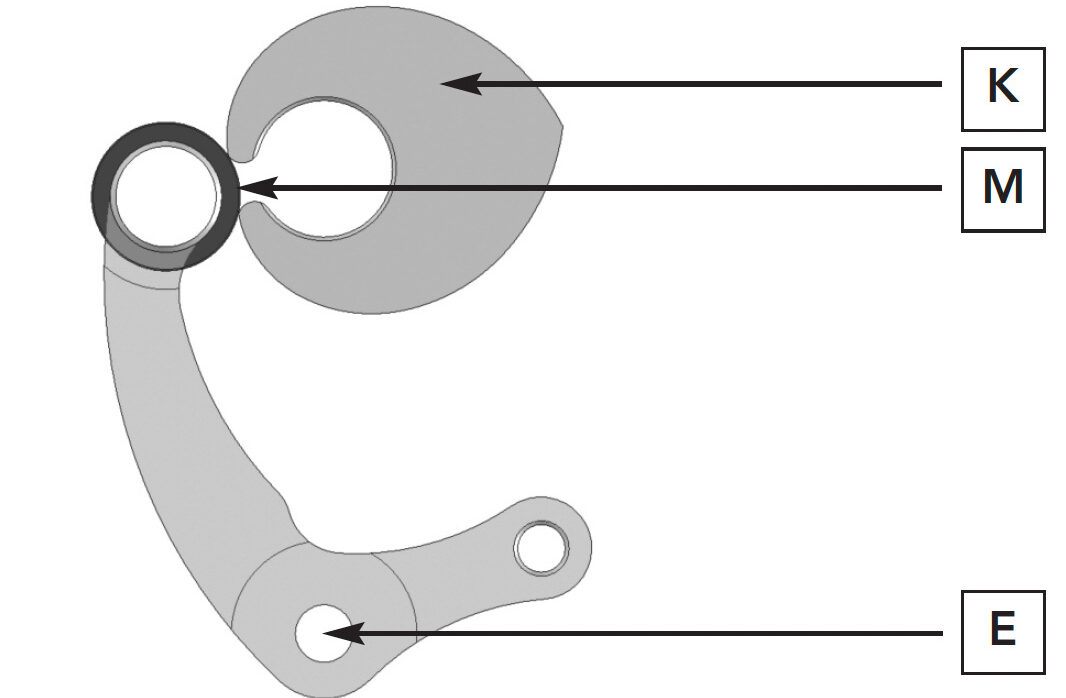

Split-seconds chronographs feature two sweep hands: the chronograph hand (known as trotteuse) and the split-seconds hand (rattrapante). The split-seconds wheel, together with the split-seconds hand, rotates alongside the chronograph wheel to which the chronograph hand is attached. Both wheels are interconnected by the split-seconds heart cam, which is mounted on the chronograph wheel. Just like in any mechanical connection, the ruby roller of the split-seconds lever requires a slight amount of play for flawless functionality. However, this play can occasionally lead to slight deviations in the position of the split-seconds hand when both hands should be perfectly aligned.

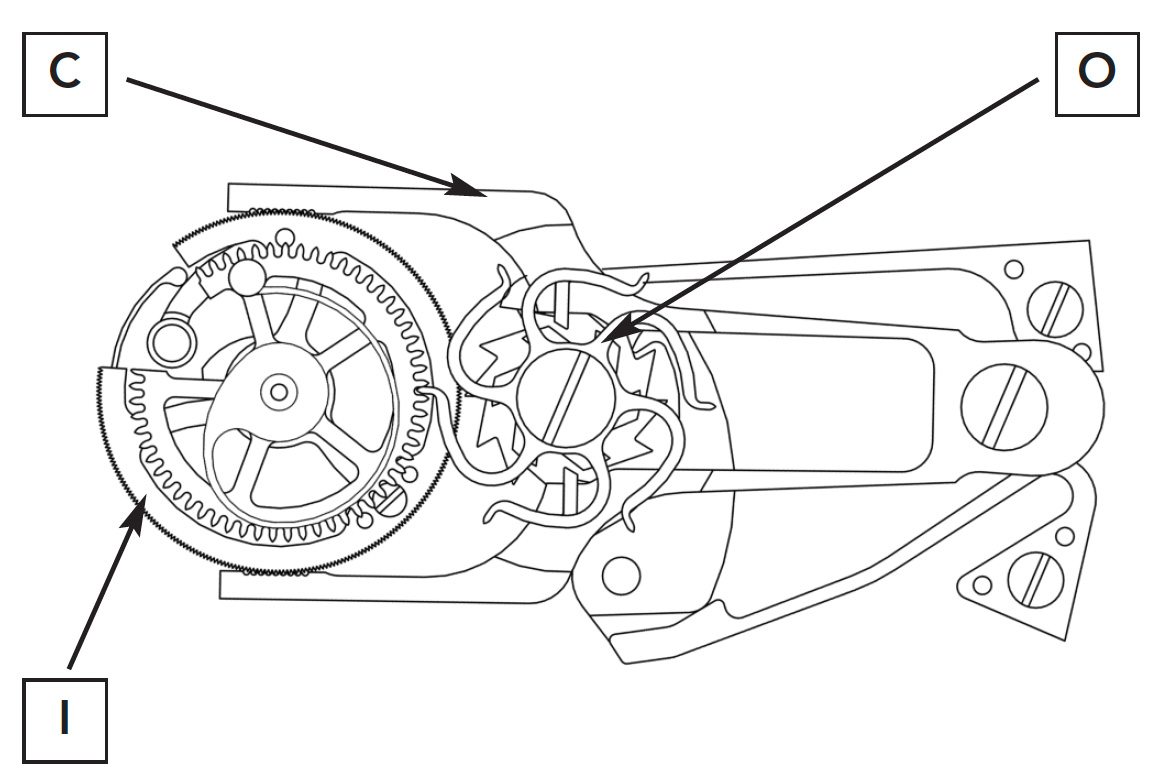

The connection between the ruby roller (M) and the heart cam (K) plays a crucial role in the functioning of the chronograph. This connection ensures that the chronograph can keep running even when the superimposed split-seconds wheel is stopped by two clamps (C) located on its side. When the split pusher is pressed, the two levers engage and halt the rattrapante wheel (I). Additionally, the isolator (O), resembling an octopus-like wheel, pushes one arm into the split-seconds wheel.

The reason behind the chronograph’s ability to continue its movement despite the seizure of the rattrapante wheel lies in the interconnection between the two wheels. The chronograph wheel is linked to the heart cam beneath the rattrapante wheel. Within this heart cam, there is a notch where a ruby roller responsible for driving the rattrapante wheel is positioned. When the clamps capture the rattrapante wheel, the ruby roller disengages from the notch, allowing the main chronograph wheel to continue its movement while the rattrapante wheel remains halted.

The heart-cam, ruby roller (left). The Isolator, rattrapante clamps and wheel (right). Source: Patek Philippe

The ruby-roller is continues to run along with the heart cam and is connected to a spring. When the rattrapante pusher pressed once again, the roller enters the notch, and the tensed spring snaps the rattrapante wheel to catch the chronograph hand.

The Isolator is the guardian of the mechanical amplitude, hence accuracy, while all of these happen. The octopus just detaches the rattrapante wheel completely, hence removes the unnecessary friction and keeps the amplitude at the desired and uniform level. Because the octopus wheel consistently rotates in the same direction, it always has to be returned to its home position together with the split-seconds lever; this is done by the isolator wheel spring as soon as the split-seconds clamp opens again.

Fitting a split-seconds chronograph into such a small diameter, within a movement originally not designed for a rattrapante function, is truly a work of art. Whether we consider the engineering aspects or the craftsmanship involved, it is an impressive feat. When we reflect upon the movements created by renowned Swiss watchmakers of the past, such as Victorin Piguet and Louis Elysée Piguet, it becomes evident that such achievements were possible even without the aid of computers. However, witnessing the delicate nature and exceptional aesthetic craftsmanship of this movement leads us to believe that watchmaking has indeed evolved, and for the better. This evolution is a testament to the constant pursuit of excellence in the industry and for Patek Philippe itself. For that, you just need to take a look at what the brand achieved with its modern chronographs, e.g. 5204, 5372, etc..

Parting Thoughts & Some Context

The Patek Philippe 5004 represents everything that embodies the essence of the brand. In my extensive conversations with the esteemed collector(s), @horology_ancienne, regarding German versus Swiss watchmaking and his deep dedication to Patek Philippe and the Swiss approach to craftsmanship, there are numerous factors he emphasises, among which the romantic allure and exceptional designs of Swiss cases hold a prominent place. When observing the Patek Philippe 5004, it becomes evident why he holds such a strong affection for it.

Despite my obvious love for Lange, one issue is that regardless of the watch or its thickness, you’ll find virtually the same case structure. It wasn’t until the 2010s when the brand introduced the new 1815 collection with stepped bezels that some variation was seen. Nonetheless, the level of detail and meticulousness displayed by Patek Philippe, or even Vacheron Constantin, surpasses that of Lange.

When it comes to finishing, after years of observation and comparison, my thought is that A. Lange & Söhne’s movement finish is indeed superior to Patek Philippe’s up to a certain point. Just compare an early Lange 1 or a chronograph from the 2000s with Patek’s offerings in the same price range, and the difference is stark. However, when it comes to higher-end price points, Patek Philippe excels in architecture, craftsmanship, and certainly technicality (which deserves its own article). The 5004A exemplifies this with its impeccable finish and brilliant architecture.

Perhaps we will delve further into these topics in the next article!

His holiness. From the inimitable bexsonn.com

Well done on making it this far. Suffice to say, it was a long read but one that we hope is as rewarding as watching a sunrise from the top of the world, which coincidentally is what we think of ref. 5004 – the Mount Everest of Haute Horology. Reaching the summit is a great goal but we know it’s all about the climb. Putting 407 parts inside a 36.7mm case and making them tick is like the ascent, one that wouldn’t have been possible without the many years of experience and others paving the way. This article itself, would also not have been possible without the many other great watch historians and writers who we are immensely grateful for.

Thank you for reading and your time.

Please don’t hesitate to contact for your comments, or if you’d like to add/substract anything from the article.

Some further reading:

- Every Instagram post from @horology_ancienne but particularly on this gem and the same collection

- Amanico’s extensive review of Patek Philippe 5070, here.

- Revolution Watch / Wei Koh’s walkthrough of Patek Philippe Chronographs, and Perpetual Calendars: here and here

- Hodinkee’s Reference Points: Understanding Patek Philippe Perpetual Calendar Chronographs

- Collectability’s series on Victorin Piguet and Valjoux

- Various, early auction catalogues

From Alp: My sincerest gratitudes to my dear friends @happy60mins for his incredible photography and eloquent writing and @watchcandies for generously donating his gem for us to drool upon!

In case you’d like to get in touch, please don’t hesitate to reach out via alp@langepedia.com.

Join Hundreds of Other A. Lange & Söhne and Watch Enthusiasts

Be the First to Know the Rare Pieces at the Marketplace, Always Stay in the Know.

Please feel free to contact:

Follow Langepedia on Instagram:

Watch “A. Lange Story” Documentary, in partnership with WatchBox:

STAY IN TOUCH

Sign up for the newsletter to get to know first about rare pieces at Marketplace and in-depth articles added to the encyclopedia, for you to make the most informed choice, and first access!