A. Lange & Söhne Grand Complication

On September 20, 2001, a very ordinary Thursday, a young couple visited the A. Lange & Söhne manufacture in Glashütte. They brought with them a “broken” pocket watch, commissioned by their neighbor, to inquire if it was worth repairing. That day, the couple didn’t receive an answer as the assessment was beyond the first impressionist’s expertise. The inspector only knew from its ornate and heavy appearance that the watch was valuable. Indeed, even back then, just like today, you could feel the difference in Lange watches with the instant heft. Following the inconclusive encounter the watch was placed in a safe, awaiting inspection by Jan Sliva, head of Lange’s antique watch restoration department.

The next morning, a colleague called Sliva: Someone brought a pocket watch yesterday. It looked valuable. I put it in your safe.

As an antique watch restoration expert, this was Jan Sliva’s first encounter with such a heavy pocket watch, even by A. Lange & Söhne’s standards. The case, too, was more richly decorated than most other models I came across for the last 20 years, says Sliva, in the book dedicated to this pocket watch. After an initial examination the next day, Jan Sliva discovered the inscription “No.42500” on the movement plate. Lange had always kept original archives and sales records of all their watches and movements, so Jan Sliva immediately contacted the Glashütte Watch Museum director Reinhard Reichel, who retired only a few years back. On the other end of the phone, Reichel was surprised – Number 42500 you said? Hold on a moment.

A call came back to Sliva, with Reichel on the other hand:

- You do not have this watch with you, do you?

- I do, it is on my bench.

- Unbelievable

Sliva was looking at the most complicated pocket watch ever made by A. Lange & Söhne with perpetual calendar, split-seconds chronograph with foudroyante seconds, grand & petite sonnerie as well as minute repeater.

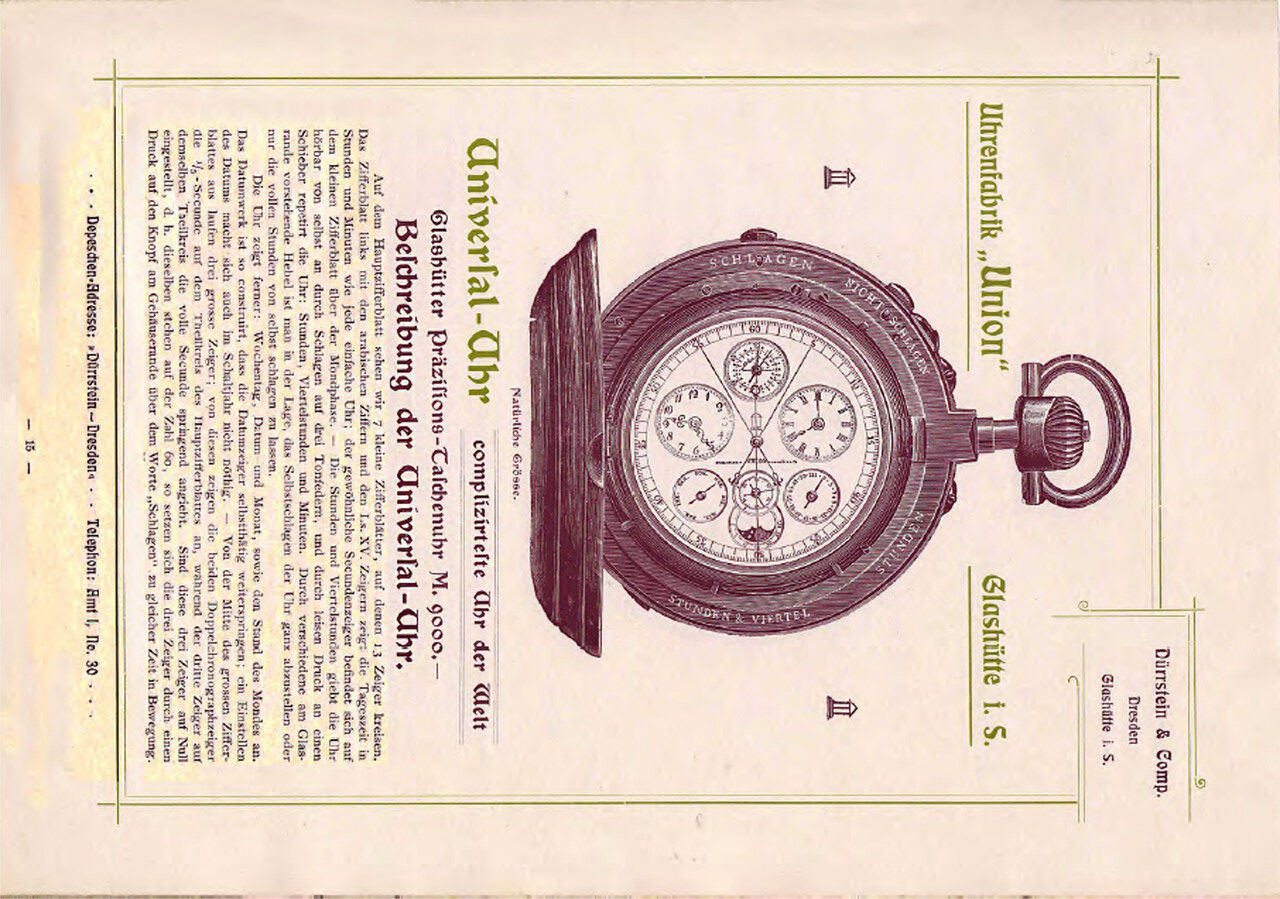

A Lange & Söhne Grand Complication 42500. Courtesy of Lange Uhren GmbH

This pocket watch, numbered 42500, was produced in 1902. It was sold on August 4, 1902, to Heinrich Schafer in Vienna, Austria, for 5,600 Deutsche Marks – a price that could have bought a villa in Dresden, the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony where Lange was located (for comparison, a basic Lange 1A pocket watch cost 450 marks, and a 1C pocket watch 250 marks at the time).

The lady who brought the pocket watch had worked as a housekeeper during WWII, diligently serving her upper-class female employer for many years. Later, her employer gifted her this pocket watch as a reward. Although the watch was already broken at the time, the employer believed that even if the watch didn’t work, its heavy gold case would still be worth a considerable amount. Fortunately, unlike most people during the war who melted valuable gold watch cases into gold bars to exchange for bread, this lady kept it in a box in her basement until it was sent to Lange decades later. They were just curious if it can be done anything about it, or should they just melt it away.

This exceptionally precious pocket watch represented the highest standard in Lange’s watchmaking history. Next morning, Hartmut Knothe, gave the lady a call, asking her to sit down first. Went onto explain: The pocket watch you entrusted us is a very special piece. Absolutely irreplaceable, it is an object of cultural value. However, it is in really bad condition, and we kindly ask your permission if we can look into it to repair. The lady approved. That approval was a song to my ears, says Sliva.

With oil leakge, rust on almost every steel component, with few broken pieces in between.

Under Jan Sliva’s leadership, Lange formed a 5-person restoration team, which took 7 years to fully restore “No.42500”. Started from 2003 and finished in 2010. To truly understand the A. Lange & Söhne’s Grand Complication wristwatch, we must first deconstruct its patriarch, just like Sliva did – but it is not going take us 7 years.

A. Lange & Söhne and Sliva’s team did a perfect job on that and published a book, documenting the steps. Just phenomenal job and a huge applause to the brand’s team for undertaking such a monumental work.

Reverse Engineering & Restoring & Reviving

Jan Sliva started dismantling the 42500… Starting from the 7-part enamel dial, separated by thin German Silver rings. Luckily, the dial was in great condition. The movement followed. An amorphous mass as described, full of rust and oil leakages. Before proceeding further, I must make a note.

Even today, making of a repeater or a Sonnerie is an incredibly challenging undertaking. There is a reason why Patek Philippe’s or Audemars Piguet’s repeaters are at an exceptional level, or why many “independent” watchmakers rely on outsourced movements should they take the challenge of introducing a repeater or a Sonnerie watch. One of the most delicate parts of construction the mechanism is the craft of gongs. Jan Sliva says: In the whole world or through my years, I could not find a person who made them. What decided how the strike would sound? What weight, material and shape? It was the ultimate misfortune when I saw the broken gong.

It was the same back in the days. There were only a handful who could craft repeaters and Sonneries, and Lange was not one of them. The movement of the grand complication 42500 comes from the famed watchmaker Louis Elysée Piguet, ordered through Audemars Piguet which explains the “JAP” markings on the gong. The movement Lange had purchased was part of a 6 calibre series ordered from the famed maker for the 50th year of the foundation of the Glashütte Watch Industry by Ferdinand Lange. Other 5 were encased and finished by “Union” Glashütte, which one superb example lies today in the AP Museum as the Universelle.

The Universal-Uhr commissioned by Union Glashütte to Louis Elysée Piguet.

The painful condition of many gears, surfaces, covered in oil like butter in a Mediterranean Summer presented a philosophical question. When should Sliva’s team try to rescue a part, restore it or create an as possible exact copy? The restorer’s dilemma… It was going to be decided as it went on. For the project, Sliva’s team prepared numerous special tools and processes to work as delicately as possible on the movement. It took three months just to disassemble the whole movement.

Albeit the modern technology was at use where necessary, Sliva’s team had to make many, many adjustments for differing screws, pinions and gears mostly on the lathe. This movement was done by the finest specialist of its time and finished by craftsmen who spent their whole lives on specializing a certain part. It took years and many hurdles along the way to craft some components by hand, in the exact form of 100 years ago. From the tiniest of screws to rattrapante gears and of course, the gong and hammers. However, in 2010, it was finally done. When asked if it is the same watch, Jan Sliva mentions the following:

“I am often asked whether it is still the same watch as before. After all, in many respects, restoration has been almost the same thing as making a new product. For me, there is not a moment’s doubt about the answer. This watch is the same one that left the manufactory of A. Lange & Söhne in the year 1902. The majority of its components are still original. Even in its outward appearance, nothing has changed. The same dial; the same case; the same crown. But most important of all; the same soul still inhabits it.

Almost surreal to see the amorphous mass above transforming to this. Courtesy of Lange Uhren GmbH

This watch is still the embodiment of what its makers conceived so long ago. It still bears witness to the summit of what could be achieved in the making of mechanical watches by hand. And pocket watch 42500 still recounts the passion and perfection of which people were capable a hundred years ago.”

And this watch, in itself, was possibly the biggest and most public R&D project for A. Lange & Söhne. With the learnings honed from this marvelous art piece, a modern example was born, and it inspired a few others along the way.

A. Lange & Söhne Grand Complication - 912.032

The most complicated A. Lange & Söhne wristwatch.

From its dial to its movement to its case.

Also the most elaborate one with black polish on all imaginable surfaces.

Also the biggest one.

50 mm x 20 mm.

A. Lange & Söhne Grand Complication. Grande & Petite Sonnerie, Rattrapante with foudroyanté seconds, perpetual calendar, minute repeater

In 2013, three years after the finish of the restoration work done on the 42500, A. Lange & Söhne unveiled the most complicated watch of its modern history. From a brand who already presented pieces like Tourbillon Pour le Mérite, Double Split and Zeitwerk and, the most complicated means big deal. And as if the watch’s formidable size was not enough, the brand put up a giant model during the SIHH to further stun the visitors.

A. Lange & Söhne produced only 7 of these gems in a span of 7 years, the last one selling in 2020. 1 stays in the manufacture as Number 0, while the rest is residing within the world’s most prominent watch collections. The price? €1.9 Million at the time. For context, Patek Philippe’s Skymoon Tourbillon was at €1 Million, and Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Hybris Mechanica at €1.8 million.

A Hero Product, as referred to it by Wilhelm Schmid in the Hodinkee interview. This is our answer to people saying, ok! A. Lange & Söhne is good, but what are they really capable of? He further opens up to Stefan Thomke in his HBS case, We knew that the Grand Complication’s price would not cover our costs. But the watch was strategic for us. We wanted to blow people’s minds, prove what we are capable of, that we belong to the top tier. Any remaining doubters were silenced with such a model. Plus, it’s a perfect fit with our brand, given its link to our pocket watches, and the technical expertise we gained benefits all our future developments.

A. Lange & Söhne Grand Complication caliber L1902. Black Polish extravaganza.

Tony De Haas, the veteran product director at the brand now for more than 20 years looks at it from a more engineering perspective, partly alluding to my R&D comment made above, We could buy a movement blank from Switzerland, but we wanted to build the know-how in-house, he says.

Well, let’s dissect this piece of art and see for ourselves, what is really going on?

A. Lange & Söhne’s Grand Complication is made of pink gold, measures at a 50 mm x 20 mm in size, and houses the same complications as its inspiration: Grande & Petite Sonnerie, minute repeater, rattrapante chronograph, foudroyanté seconds (activated with the chronograph) an instantenous perpetual calendar and a Moonphase.

The chronograph / split-seconds chronograph work with the pusher at 10 o’clock and 1.30 o’clock as a monopusher-rattrapante, again, first of its kind at A. Lange & Söhne. As you activate the chronograph, the foudroyante starts flowing, offering quite a spectacle. The repeater is operated via the slide looking pusher at 7. And finally, the Sonnerie is controlled via the switches at 12 and 6 positions, as silent mode and switch between petite & grande sonnerie, respectively.

Courtesy of Lange Uhren GmbH

Its pink gold case is one of the first exceptions, featuring a brushed mid-section. Until this piece, and longtime afterwards, all pink gold case Lange pieces (except the custom pieces, etc.) featured a fully polished band. The rationale here is surely to give an aesthetic distinction to a 20 mm thick case. Overall, we see the classic Lange case construction with three-layers, steeply angular lugs to compensate the thickness, and of course a few more pushers than usual for the rattrapante, repeater and Sonnerie.

The protruding case back is so deep, despite the curvature of the lugs they still float at about 2 mm above the wrist level. I would not assume anyone’s priority would be comfort at this magnitude, but even if it was, the piece is indeed quite wobbly on the wrist and requires a solid strapping down.

On the bezel side, we witness a remarkable depth while travelling through the dial. The stacked rattrapante hands require quite the space, delivering a tremendous three-dimensionality, further enhanced by the sunken enamel sub-dials. The vast dial rehaut is not wasted. Inside, an elaborate A. Lange & Söhne engraving at 12 o’clock.

Courtesy of Lange Uhren GmbH

The Dial

A triumphant reincarnation.

No frills, no-nonsense, as loyal as it can be to an early 20th century pocket watch, but modernized to perfection with a color palette better than Bob Ross’.

The 1815 Collection itself is a perfect summary of the brand’s design route. Take inspiration, but at all costs, do not copy. Lange succeeds this with modernized numerals, cleaner lines, stronger hands, and overall, a specialized typography. The Grand Complication looks back to 1902, respects its forefathers and beams it to the 21st century.

The A. Lange & Söhne Grand Complication wristwatch starts by merging the two-step seconds and minute track into one railway track, with added beat-matching chronograph seconds hash-marks. Further inside, we see modernized Arabic numerals, adorned with the brand’s typorgraphy. The sunken enamel sub-dials are delightfully in their places, adding a tremendous depth to the busy dial, offering the information at various levels. To my knowledge, this was the brand’s first in-house enamel work, which laid the foundation for future models – most prominent one being the inimitable Lange 1 Tourbillon Handwerkskunst.

Courtesy of Lange Uhren GmbH

The hands are the brand’s signature alpha-hands, with more contrasting colors given to rattrapante seconds and minute hands. The foudroyante is merged with a translucent blue Moonphase indication. At the 12, quite an unusual month indication, encompassing 4 years great us with a matching leap-year indicator inside and chronograph minute counter at the outer chapter.

Another delightful detail is the German day and month indications. The German inscriptions lift its historic soul, adding one more concrete connection to the brand’s proud early 20th century. We see the gold, red and blue as the dominant colors, bringing together a timeless look. The numerals, lines, markers just float above the enamel with very slight imperfections up-close, reminding you the painstakingly human work behind.

The Most Complicated A. Lange & Söhne Caliber L1902

From the very start in its modern history, A. Lange & Söhne has always been about showing what it can do. The inimitable Tourbillon Pour le Mérite, the world’s first wristwatch combining the tourbillon and fusée and chain mechanism and possibly the most important modern reference of the brand, was a signal of what is to come. It was a signal to collectors that they can indeed count on the new team with Walter Lange and Günter Blümlein to revive the brand to its further glory and beyond.

The Sax-0-Mat followed not long after, with an exquisite three-quarter solid gold rotor, an exceptional movement architecture in a slim package and of course the zero-reset function. To this day, considering the price too, I am still adamant that this movement was the best self-winding calibre that came out from the Saxon.

The turn of the millenium brought us the Datograph.

A flyback chronograph with a movement finish, architecture and aesthetic that in my opinion is still unmatched. The very watch that got me into watches 15 years ago when I stumbled upon an incredible capture of it at the purists forum back in 2010…

In 2004 we got the one and only Double Split. The world’s first double rattrapante wristwatch. A mechanical jungle on the back, a doorknob (thanks for the term @herrmorgensonne) on the wrist, with a dial as deep as its movement… Then the Cabaret Tourbillon, the Zeitwerk, etc.. Long story short, when it is the most complicated A. Lange & Söhne, it means something!

A rattrapante chronograph, Grand & Petite Sonnerie, Minute Repeater, Foudroyanté seconds, an instantenous perpetual calendar, and a Moonphase.

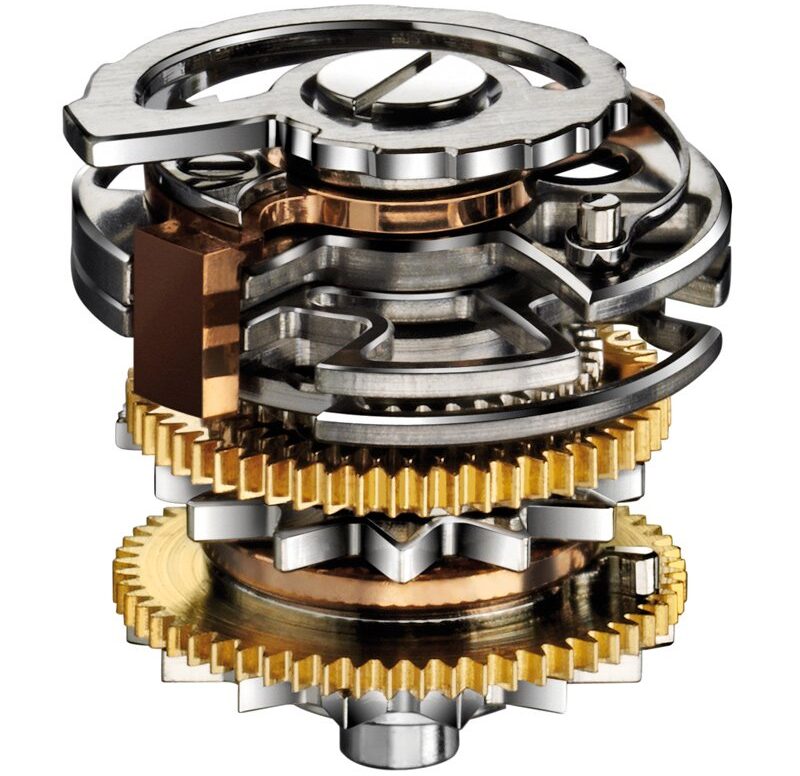

The energy system is built over three barrels, each providing separate energy for timekeeping, rattrapante chronograph with foudroyanté seconds and Sonnerie. 30 hours of power reserve for the former two, and a separate 24 hours of reserve for the Sonnerie and repeater.

876 individual parts.

The rattrapante chronograph + foudroyanté occupies 248 parts in total and can be viewed from the backside of the watch.

When the pusher at 2 is pressed, the chronograph hands + the lightning seconds start to run. Upon pressing the rattrapante pusher at 11, the gold hand stops while the blued rattrapante hand continues to run. Another push catches up the hand again. Pressing the 2 o’clock button once again stops all four hands, and one more push resets the hands.

As most of you know, I like to go into the movement, and understand how all this 248 parts work in harmony! Thanks to the foudroyanté, this is especially fun!

The section below is written with the help from the book:

Upon pressing the button, the actuating lever (1) moves through a rocker. At its end, a movable pawl slides across a tooth of the column-wheel (2), thereby the column-wheel is moved by one tooth. Please note, the column-wheel has two sets of discs at the upper and lower levels. Each set of discs is comprised of five notches, connected to different levers. One of these is the clutch lever (3).

With one arm, it engages in the centre disc of the chronograph column wheel. On the other arm is a slightly higher gear wheel that can turn freely. This whole assembly is preloaded in the clockwise direction. When the arm of the clutch lever falls into a notch in the disc, the assembly moves clockwise, and the upper gear wheel engages simultaneously with wheels (4) and (5). The upper wheel (4) can turn freely. It lies directly above wheel (5) and has the same toothing. The two wheels are coupled together through the upper gear wheel when this swivels in.

The upper wheel (4) is mounted on a long tube that carries the chronograph hand on the other side. The lower wheel (5) is incorporated in the power train of the chronograph. As soon as the chronograph is started and the clutch lever (3) connects the two wheels, the chronograph hand also starts.

First, however, the zero-reset lever (6) must decouple, as otherwise it would block the zero-reset heart cam (7) which is fixed to the chronograph wheel. And again, this movement is controlled by the column-wheel spinning.

The upper disc of the chronograph column wheel is responsible for starting and stopping the movement and for resetting the lightning seconds to zero. All three functions are relayed by this disc through the lever (8) to the wheel (9).

This lever (8) is spring-loaded anticlockwise and is pressed outwards clockwise by the upper disc when the chronograph is started. This action also moves the pawl of the lever outwards, releasing the star wheel and, thus, the whole chronograph movement.

The star wheel is also a central and complex component. It consists of two five-pointed star wheels, which are positioned one above the other and connected by a pin in the upper star-wheel and a groove in the lower one. The upper one is mounted on an arbor, which passes right through the movement and carries the lightning seconds hand on the dial side.

The star-wheel for the foudroyanté, with rattrapante block in the center, two-step column wheel on the right. Courtesy of Lange Uhren GmbH.

When the chronograph starts, both star wheels of the wheel make one revolution per second. In this process, however, they are stopped and released again five times per second. This is performed by the lower star-wheel, which engages its teeth with the 30-tooth wheel (10). This wheel is solidly connected to the escapement wheel and performs one revolution every six seconds, hence the ratio of 1/6 seconds measurement on the foudroyanté.

The stop, reset and the rattrapante mechanisms of the movement is quite traditional. While the former two relies on the backwards process, and heart cam mechanisms (except foudroyanté has its own mechanism for reset) the rattrapante function relies on the second column-wheel and pincers that catches and releases the rattrapante hand.

For more explanation on how the rattrapante works, I kindly recommend you read the in-depth read on A. Lange & Söhne Double Split.

The Sonnerie & Repeater Mechanism

Of course, what makes this grand complication “grand” or any manufacture a high-end manufacture is the Sonnerie and Repeater sections. The legend of early watch forums, Carlos Perez also points out, dual train grande sonneries merit “grande complication” status in their own right.. No wonder, even in modern times, you either rely on specialists like Claret or you are one of the very very few who can put out something like this in-house.

A. Lange & Söhne is proud, rightfully so… The caliber L1902 is the first ever completely in-house Sonnerie movement made in Germany. Walter Lange saw with his own eyes that the modern manufacture lived up to the expectations and goals of his great-grandfather, perhaps even exceeded. Glashütte indeed became the epicenter of watchmaking in Germany, and for a sizable population.

The Sonnerie and Repeater movements are hard to explain. One cannot help but wonder, how did the incredible repeaters, Sonneries were made back in the days without any computer aid, fully by hand. Then Dufour, who managed to craft a Sonnerie for a wristwatch. Just incredible…

I’ll do my best, again with the help from the material from the book.

This watch’s strike train operates independently from the main timekeeping and chronograph trains, drawing its energy from a separate barrel that is wound by turning the crown counterclockwise. This isolated power source ensures that chiming the time does not affect the accuracy of the watch’s going train or chronograph. It has its own escapement (or governor if you will) for the pacing and sequencing.

Another reason for the separate train is of course the energy management. In full strike mode, the (Grand) Sonnerie automatically strikes hours and quarters. Understandably, the movement of tens of parts, and the rather heavy hammers drain significant power, hence the reason for the separate train to ensure accurate timekeeping.

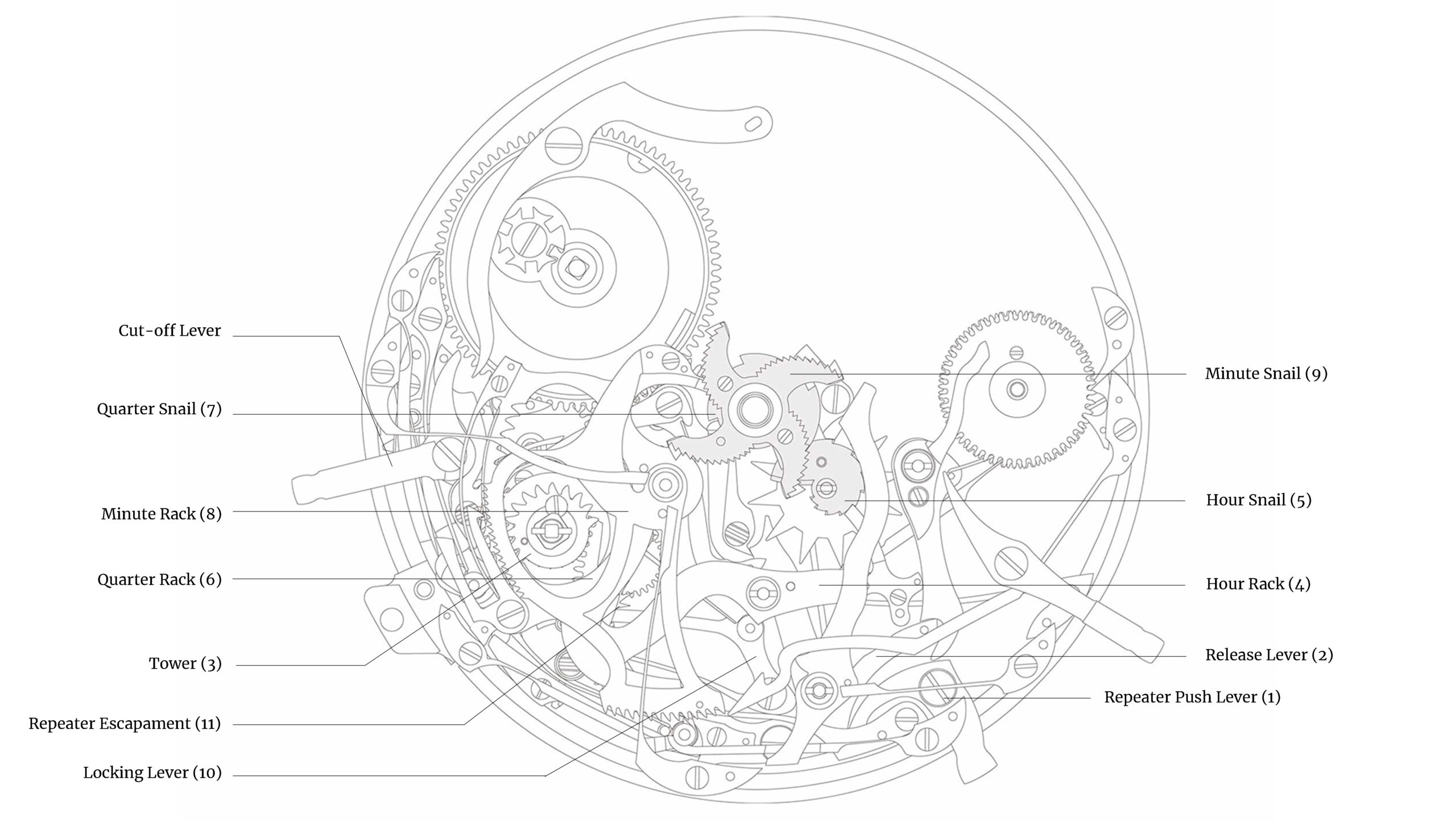

With the help of the diagram below, let’s try to understand the chain of events when the pusher is pressed or during the Sonnerie sequence.

As soon as the repeater slide is pushed, a lever (1) pivots and nudges the release lever (2). This lever has a spring-loaded beak that engages with the lower ratchet wheel on the underside of the “tower” (3), a multi-level assembly that sits at the heart of the striking mechanism. The tower itself is engineered to act as the distribution hub for the racks that measure the hours, quarter-hours, and minutes to be struck.

That initial nudge of the ratchet wheel shifts the lower portion of the tower slightly anticlockwise. This, in turn, unlocks the upper portion, allowing assemblies such as the hour and quarter segments to rotate freely on their sleeve for the duration of the striking sequence. Almost instantly, the racks—spring-loaded arms equipped with sensing fingers—are let loose to “read” the current time from precisely engineered snail wheels.

The multi-step tower mechanism, the brain of the striking complication. Shown here is from JLC’s Hybris Mechanica Sonnerie

First, the hour rack (4) drops against the hour snail (5), which features 12 distinct steps, one for each hour. Whichever step the rack’s sensing finger lands on determines how many times the hammer will strike for the hour count. In the next moment, the quarter rack (6) falls against the quarter snail (7). It, too, sees only as far as the time indicates: zero, one, two, or three quarters. Finally, the minute rack (8) is released—unique to a manual repeater—so it can drop against a snail (9) whose four “arms” each have 14 teeth, allowing for minute strikes from one to fourteen if needed, thereby covering the minutes between the quarter marks.

While the racks are falling, another crucial element is at work: the locking lever (10). This small lever keeps the pallet fork of the striking train locked until all racks have completed their fall. Only when the minute rack is in place (or deemed not needed for a passing quarter strike) does lever slip out of the way. At that moment, the escapement (11) of the striking train is freed, letting the tower begin its controlled rotation powered by the separate barrel.

The chiming sequence always follows the same order: hours first, then quarters, and finally minutes (if the watch is striking in full repeater mode). During this process, the hour segment (in the tower rotates, and each of its teeth passes a “generator” on the opposite side of the plate. A generator is a small rotating component fitted on the arbor that also carries a hammer. Each full rotation of the generator lifts the hammer and releases it against the gong, producing a single chime. After the hour count is concluded, the quarter segment takes over, and the quarter rack (is gradually lifted back as each tooth slips past another generator, creating the familiar ding-dong pattern of a quarter-hour strike. Finally, if minutes are to be chimed, the minute rack is also lifted back up to its resting position, passing yet another generator, delivering up to fourteen additional strikes to count out the minutes beyond the last quarter.

Throughout this process, the chimes are precisely paced by an escapement system—complete with an escape wheel and pallet fork—dedicated to the striking train. This ensures a regular, measured tempo of the watch’s gongs, preventing rapid or uneven striking. Once the final hammer blow has sounded, the rising racks push the locking lever back into place, immobilizing the pallet fork again and ending the chiming sequence. The tower, racks, and levers reset to a locked position, standing ready for the next quarter-hour passing strike or a future press of the repeater slide.

You can see the tower on the left, minute and hour snails towards the middle. Courtesy of Lange Uhren GmbH

The Sonnerie is an incredible choreography of snails, racks and levers, working at the minimum tolerances one can imagine in watchmaking. It is truly the culmination of one’s watchmaking mastery, a true test if you will, and a true pride for every manufacture who have the knowledge to craft and assemble one. The highest echelon of watchmaking for sure.

As the brand always does, the user experience is at utmost importance, hence there are certain developments to cater that philosophy. The Sonnerie has a safety mechanism, which allows you to adjust the time during striking. Later on, we can also recall this from the Zeitwerk Minute Repeater.

The finish on this gem is extraordinary.

Every steel chronograph component is black polished. A mind-boggling process, which one small mistake or a dust particle can ruin a component that you worked hours for, and that is applied to more than 200 components. The contrast against the warm German Silver is just delightful, not to mention the signature red rubies, gold chatons and blue screws. Wheels are made of gold, and the Glashütte escapement is specially placed to honor the predecessors of this one-of-a-kind masterpiece.

Indeed, it does show what A. Lange & Söhne is capable of when it comes to handcraft. Please note, following this gem, we got Handwerkskunst editions like 1815 Tourbillon and Lange 1 Tourbillon Handwerkskunst, which in my opinion are the most lavish pieces came from Glashütte.

A recently, privately sourced and sold Lange 1 Tourbillon Handwerkskunst. The best finished Lange there is.

But, despite all its glory and lavishness, where does the Grand Complication stand? Is it truly a triumph?

In my opinion, it is an ambitious start and a milestone for bigger things.

When we walkthrough the movement, you could easily see the replication of the pocket watch movement. Fundamentally, the A. Lange & Söhne’s Grand Complication wristwatch is a product of reverse-engineering, standing on the shoulders of its Swiss craftsmen. That partially explains the behemoth size of the wristwatch at 50 mm x 20 mm. It does not contribute much to the modern watchmaking innovation nor houses something “more” from its predecessor.

Yet, there are still admirable parts on the creation of it. Indeed, in its entire existence from 1845 to 1945, A. Lange & Söhne possibly produced around 700 repeater watches, most of them being quarter repeaters. The most complicated pieces almost always arrived from third-party movement specialists. Please note, the same case applies to Swiss brands too, as the watchmaking was based on the etablissage system. The difference was, Lange had to order from Audemars Piguet to access Louis Elyseé Piguet whereas the Swiss manufactures had direct access to the specialists, hence the developing know-how. Against this rather weaker (compared to established Swiss brands) background, A. Lange & Söhne made a huge stride with the Grand Complication, and that I applause. That is not only telling what the brand is capable of, but telling where the brand is heading to and the long-term vision.

A. Lange & Söhne did not choose to outsource the enamel dial, the gongs, the repeater ebauché or the foudroyante mechanism. They insisted on building all themselves, and that eventually led to pieces like Lange 1 Tourbillon Handwerkskunst with in-house black enamel dial, Zeitwerk Minute Repeater, and hopefully one day, a Sonnerie wristwatch.

There are still a very few modern manufactures who can count a Sonnerie under their repertoire. From the godfather of the complication, Dufour’s entrance to the scene, to Audemars Piguet’s incredible feat with Carillon (three sets of hammers & gongs instead of two) Sonnerie, from Genta’s gems in 1990s made by a team led by Pierre-Golay to Journe’s novel take on the complication to Greubel Forsey to Patek Philippe and the grandest of them all, the Hybris Mechanica from Jaeger-LeCoultre…

You see, these movements are made either by the absolute superstars of today’s independent watchmaking, or the foremost names you’d think in the watch-world today. The fact that A. Lange & Söhne managed to dissect, learn, improve and build without an existing knowledge in its history represents everything this watch conveys.

What the Grand Complication represents is, as shocking as it may sound, bigger than the wristwatch itself.

Thank you.

My sincerest thanks to A. Lange & Söhne for providing in-house photos for the creation of this article. As well as my dear friend who owns one of these gems who graciously took time to share its photos with me.

Please feel free to contact:

Follow Langepedia on Instagram:

Watch “A. Lange Story” Documentary, in partnership with WatchBox:

STAY IN TOUCH

Sign up for the newsletter to get to know first about rare pieces at Marketplace and in-depth articles added to the encyclopedia, for you to make the most informed choice, and first access!