A. Lange & Söhne v Patek Philippe Part 1: Chronographs

Briefly, A. Lange & Söhne and Patek Philippe Chronograph through decades. Thank you The 1916 Company and Sotheby’s for the photos.

There are a few types of watch enthusiasts that I have observed over the years. Though this article is not the place to deliver my analysis of these segments, I’d like to simply divide the group into surface and depth enthusiasts. To each their own, and no discrimination, of course! Possibly due to my deep appreciation mainly for A. Lange & Söhne, my circle has mostly been filled with the latter, perhaps except between 2021 and late 2022, but that crowd is mostly gone. Those who go deeper stay for the fine print. Those who take the red pill and travel through the depths of watchmaking start to see more of what’s going on in the industry. Though at times unsettling, it is often rewarding, as they develop an understanding of history, finest details, and what makes them work.

Collecting has many aspects, and one central motive for many collectors is history and its continuation. There are those who simply do not care, which I respect, but I bet that any Patek Philippe or A. Lange & Söhne collector has an eye and heart for the past. It brings an emotional significance, and I can tell that the more you know, the more you appreciate the design, the evolution, and the values of the piece of art you are wearing and sharing with your friends. It brings a connection to a storied legacy, and as these pieces are extensions of oneself, most owners tend to (or want to) resonate with the ethos of the brand or the watchmaker they’re supporting.

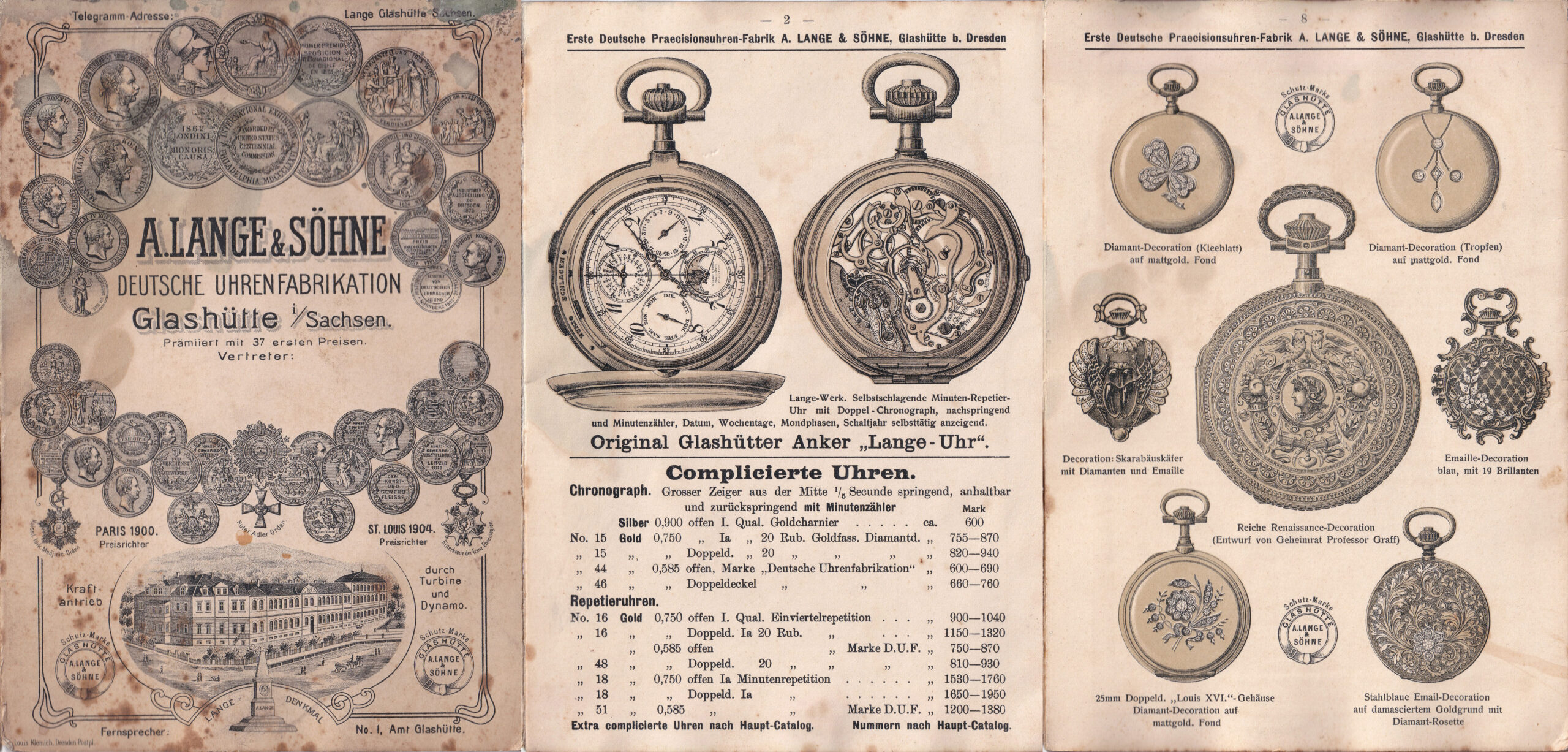

An A. Lange & Söhne Catalogue from 1900s, showcasing a Grand Complication. From the Article: A. Lange & Söhne 1845-1990

A lot of recent discussions, especially around Lange, revolve around sales practices, investment, etc. All are valid and healthy discussions; alas, I realized that they distance me from why I love the brand and watchmaking in the first place. The policies are temporary, but the heritage and craft are eternal. We’ll see those policies shifting with changing market conditions. Today, I’d like to go back to those roots, while hopefully delivering a valuable perspective on one of the questions I receive often – Patek Philippe or A. Lange & Söhne?

The watchmaking histories of A. Lange & Söhne and Patek Philippe follow entirely different paths, and this is what makes their stories and collectors so interesting. However, for the sake of brevity, I do not want to delve into the general history of each brand but rather focus on their chronographs and make our way to modernity.

Before starting, if you are interested in a general historical read on Lange, you can find it here. For Patek Philippe, a well-engaging talk can be found at the 1916 Company’s youtube channel with the guest John Reardon, here.

I wanted to divide this article into two periods: Before and after 1999. When looking at the early days, we are going to examine the two giants in the following aspects:

- A general look into pocket watches, cases, dials, and design

- Early patents / Contribution to the chronograph area

- Handcraft / Movements

For modern times, we will follow the same structure, objectively comparing Patek Philippe and A. Lange & Söhne chronographs, but of course with more material and a more technical/craft focus.

Below, please find quick links to guide yourself with ease:

Patek Philippe v A. Lange & Söhne Chronograph – Pocket Watch Days

There is a famous quote from Blümlein, co-founder of the modern A. Lange & Söhne brand. He says: “I want our watches to feel heavy and strong. You know the feeling of closing a Mercedes door? Like that!”

This quote doesn’t come out of nowhere. It has a history of 150 years. If you hold a Patek Philippe and an A. Lange & Söhne chronograph pocket watch in your hands, one thing that will immediately strike you is the weight. I’m not sure where it’s coming from, but it’s delightful. As Blümlein states, today, when you strap on any Lange watch onto your wrist, once again you’ll feel that tremendous presence.

I remember strapping on my first Lange 1 almost a decade ago, and everything else felt hollow in comparison.

The case structures are almost the same, with unique differences in decoration, perhaps a family crest, or an owner engraving, etc., usually on the back side of the watches. The dials are made of enamel with fine print, usually on a brass base, and we can see various chronograph designs – at times vertical, horizontal, center-stacked, or regulator displays.

The top row is A. Lange & Söhne and the bottom row is Patek Philippe. The difference as well as Patek Philippe’s variety is striking.

The photo above should deliver some very important hints on each brand’s approach to designing watches. Please observe how Patek Philippe utilized the classical Louis XVI hands far less than A. Lange & Söhne. Further, you might notice Patek’s chronographs appear to be on the sportier side, compared to Lange’s more traditional/dress approach. Lastly, although I cannot include all examples here, Patek Philippe offers much richer design choices than Lange, be it with sector dials, regulator dials, etc. This is interesting to see because we observe almost the same design richness from Patek Philippe vs. more restrained and fewer options from A. Lange & Söhne in modern times.

Another important point is how A. Lange & Söhne’s design language has stayed intact and differs from Patek Philippe. You can see the Arabic numerals are given a delightful flair, but not in Breguet style; it is Lange style. Today, we can see the same influence in the 1815 Collection, and for Roman numerals, in the Richard Lange collection.

When we flip these gems over and open the dust covers, you might be surprised. Because, as opposed to modern times, we are going to see a similar movement construction/finish in both brands. One very important reason for this is that most complicated pocket watch movements, even for A. Lange & Söhne, came from Switzerland.

Patek Philippe (left) and A. Lange & Söhne rattrapante pieces, with rattrapante on the top plate. Courtesy of Collectability and Sotheby’s.

The two mechanisms above are rattrapante mechanisms, with the rattrapante module on the dial side. Please observe the striking similarity between the movements/constructions. There is a fundamental reason for this apparent resemblance. Interestingly here, the one with the ¾ plate is Patek Philippe, while the one with the exposed barrel and ratchet wheel is A. Lange & Söhne – a configuration that might surprise modern enthusiasts.

The Swiss created a system that allowed them to dominate the world of watchmaking: Etablissage, or division of labor. This ingenious system relies on each specialist doing their own specific work, to be later finished, decorated, and assembled at the brand’s premises, under the brand’s name. In other words, the quality of one’s watches was largely determined by the expertise of its suppliers!

Patek Philippe (and A. Lange & Söhne later) greatly benefited from such a doctrine. According to John Reardon of Collectability, as early as 1841, Patek would purchase blank repeater movements from the renowned (Victorin) Piguet family. As years went by, the relationship and expertise developed even further, bringing us nothing short of watchmaking marvels in the coming decades.

Ferdinand Adolph Lange’s A. Lange & Cie, on the other hand, faced a different challenge. They had to develop the industry from scratch in the rather unpopulated Glashütte region. This endeavor was so demanding that it would take Lange years to produce his first pocket watch. Indeed, his energy was primarily focused on training others in the vast universe of watchmaking, covering all aspects from cases and hands to dials, pinions, jewels, and more. His goal was to transform Glashütte into a sustainable watchmaking hub, mirroring the successful Swiss system. This comprehensive approach explains why we see the final shape of the famous Glashütte style movement – with its distinctive ¾ plate, gold chatons, blued screws, Glashütte escapement (invented by F.A. Lange himself), hand-engraved balance cock, and other hallmarks – only in 1873, a full 28 years after the establishment of the brand.

A. Lange & Söhne pocket watches from 1852 – 1866 and 1875. From Sotheby’s Masterworks of Time Auction.

In the 19th century, we see numerous chronographs and rattrapantes from both brands, executed in different styles, albeit with similar movement constructions. The common point in both is the exceptional finish. Each complicated movement from both brands is gracefully constructed and meticulously finished, to a point where one might wonder how modern watchmaking seemingly missed this level of handcraft.

However, it’s important to note that rattrapantes, repeaters, and other highly complicated watches were exceedingly rare in the early days. For example, A. Lange & Söhne produced only 34 examples of monopusher rattrapantes with the mechanism on the top plate, a few others with multi-complications, and only three with the rattrapante mechanism on the dial side. This rarity explains the incredible workmanship we see in all these horological gems.

A classic Rattrapante movement from Victorin Piguet for Patek Philippe (left) and a very rare dial side rattrapante from Lange

The intricate craftsmanship is immediately apparent, with delightful inward angles present at almost every turn on the bridges and levers. The black polish is omnipresent, creating a striking contrast against the Maillechort base plate along with ruby gems. Remarkably, both brands still retain some of these signature elements from a century ago. Patek Philippe’s movements feature thin levers, a delicate construction with many bridges, and a capped column wheel. A. Lange & Söhne’s movements are distinguished by hand-engraving on the balance, gold chatons, and an open column-wheel. Both are undeniably magnificent in their execution.

It’s crucial to note that despite the prevalence of outsourcing, these brands were far more than mere assembly houses. They actively developed mechanisms and claimed patents for chronometry and construction innovations, further enhancing the ebauche movements.

To illustrate, A. Lange & Söhne received a patent for the chronograph mechanism visible on the top plate in 1873, and later for the famous dead-beat seconds in 1875, which saw a modern iteration with the Homage to Walter Lange in 2019. Additionally, Richard Lange patented a rattrapante movement for one of his personal pocket watches in 1887. Across the border, Patek Philippe was equally ambitious and capable. Among their numerous patents, perhaps the most significant is the “double chronograph” in 1902 – a concept similar to the A. Lange & Söhne Double Split introduced in 2004. A pocket watch example (with an additional complication, a true triple split) showcasing this groundbreaking work recently surfaced at Phillips and sold for $1.2 million.

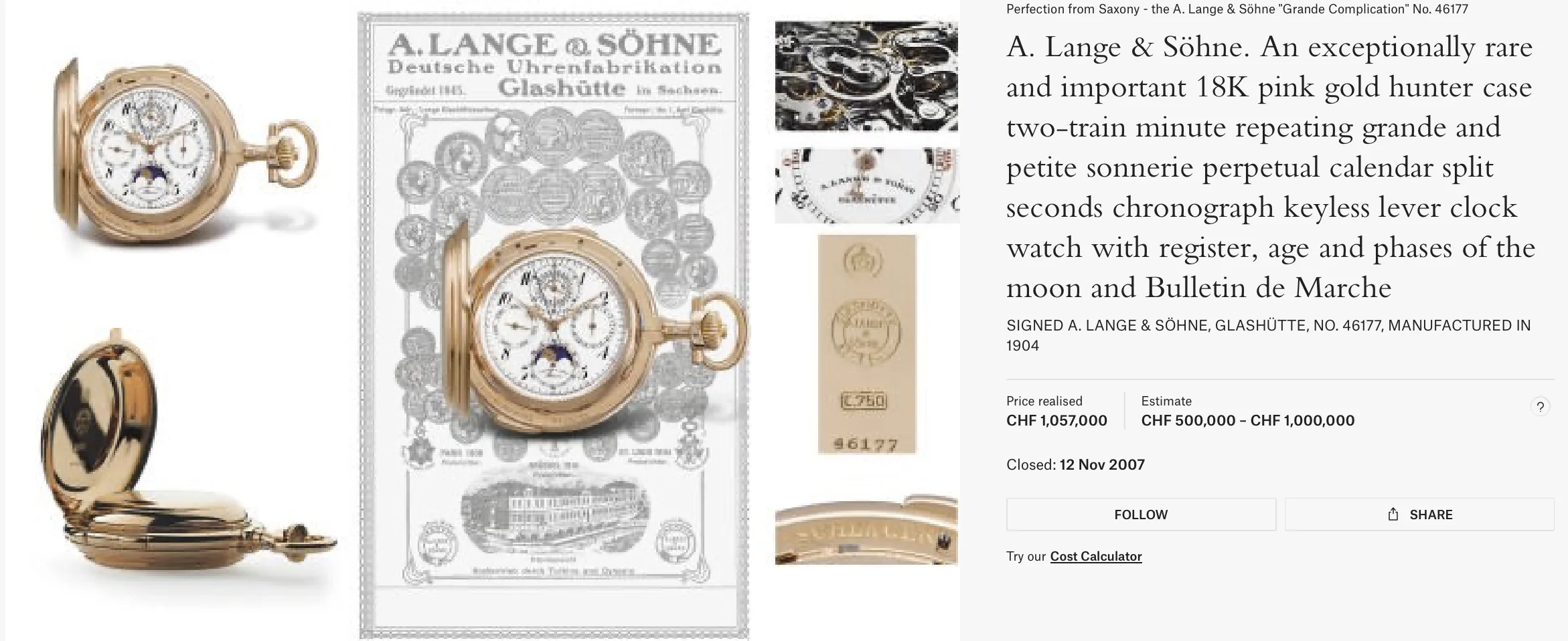

The dawn of the 20th century marked the golden years for A. Lange & Söhne. This period saw the creation of their first tourbillon pocket watches, including the “Centennial Tourbillon” in the 1900s, as well as exceptionally constructed and finished Grand Complications. A notable example is the piece sold in 1902, later restored by A. Lange & Söhne in the 2000s. Although the movement originated from Switzerland, possibly from Jules Audemars and Edward Piguet, the final product was immaculate. A. Lange & Söhne crafted only nine Grand Complications from the late 1890s to 1924. A few of these masterpieces reached auction blocks in the ’90s and mid-2000s, commanding incredible sums for a brand still in its youth.

One of the 9 Grand Complications made by A. Lange & Söhne, sold by Christie’s.

A. Lange & Söhne’s decline began in the 1910s and continued through the mid-1920s. World War I and Germany’s role in it severely hampered the brand’s ability to sell watches to its international clientele. In the aftermath of Germany’s defeat, during the Weimar Era, the brand was forced to compromise on quality, focusing on cheaper watches and reduced workmanship to survive. Sadly, the heyday of A. Lange & Söhne, which once crafted gems rivaling the best of Switzerland, was short-lived. From Ferdinand Adolph Lange’s establishment of a watchmaking industry to its decline in producing top-tier, highly complicated pieces, we’re discussing a span of merely 60 years. Once again, for more on this period, please have a read my article A. Lange & Söhne from 1845 to 1990.

Conversely, Patek Philippe continued to flourish, mirroring Switzerland’s fortunes. With a strong focus on complications and exquisitely decorated pieces bearing “EXTRA” titles, Patek Philippe supplied watches to world leaders. Furthermore, I would claim that Patek demonstrated unparalleled vision. From successfully miniaturizing complications to recognizing the advent of wristwatches, the brand consistently remained at the forefront of horological and design developments, often setting the path for others to follow. While A. Lange & Söhne’s decline began in the late 1920s, Patek Philippe’s ascendancy continued with even greater momentum.

Patek Philippe v A. Lange & Söhne Chronograph – Wristwatches

As we transition from the pocket watch era to the age of wristwatches, we are going to witness a divergence in the paths of these two. This period marks a crucial turning point in the history of both companies, shaping their trajectories for decades to come.

I often applaud Patek Philippe for the variety of designs they manage to put out. We are going to go in-depth on this topic in the coming paragraphs, but the evolution one witnesses from the 5070 to 5170 to 5172 with individual differences within the collections is mind-blowing and a treat for the collector.

Unfortunately, A. Lange & Söhne’s endeavor in wristwatches is short-lived. There are time-only pieces, made under the brand name A. Lange & Genf in Switzerland. Finally, some more as pilot’s watches during WWII as well as a few commercial ones during the late 1940s before the expropriation of the company by the Soviets. Even under the direst circumstances of Glashütte and Germany overall, however, you still see the workmanship in the movements, perhaps putting the last ray of sunshine into these gems before the Eastern Germany is formed. As this era does not feature any chronographs for A. Lange & Söhne, I am going to dive straight into Patek Philippe.

Patek Philippe’s first wristwatch chronograph is a rattrapante gem, which later gave inspiration to the modern marvel 5959. Based on a Victorin Piguet ebauche, at an incredible size of 33 mm. Starting from the mid 1920s, we see numerous references with various case and movement designs from Patek Philippe also with different movements outsourced from the likes of Victorin Piguet, Valjoux and Lemania. Just like the pocket watch days, Patek Philippe would acquire movement blanks from the suppliers, and finish, improve them to meet its own superlative quality

Vintage Patek Philippe Split-Seconds wristwatches. From the article: The Story of a Legend: Patek 5004A

A showcase of Patek Philippe’s workmanship over the ebauché, on the far right

When examining Patek Philippe’s rendition of the Valjoux 23, one cannot help but admire the exceptional finishing work. The presence of inward angles, a flat polished escape wheel cock, and a cap on the column wheel exemplify the meticulous attention to detail. Additionally, the brush finish on the chronograph levers and the polished screw slots further enhance the overall aesthetic.

It is the boldness in design starting from the mid 1920s, to the first serially produced chronograph wristwatch reference 130 in 1937 to mid 1960s with the reference 1463, that still inspires Patek Philippe’s modern chronograph façades. Indeed the 50s and 60s brought us brilliant designs across different Swiss Watchmakers, but looking back today, I see that Patek Philippe caught the timelessness perhaps better than anyone else. So much so that we see numerous “homage” watches utilizing Patek Philippe’s lines from those days. The selection above is just a very small sample, but if you’d like to have a better idea, I highly recommend you visit Wei Koh’s article, here.

The cases, bezels and pushers are other notable points. You see the Genevan flair when you look at the flowing structure. The variety continues here too, mainly with the lugs, bezels and pushers: Spider, curved, thick, straight – rectangular, pump, round pushers…

A few vintage Patek Philippe chronograph cases. Brilliant variety, still an inspiration. From Sotheby’s Archives.

One very interesting example in the brand’s repertoire is the reference 2512. Made in 1950 and sold in 1952, at 46 mm it would only suit the pilot’s wrists during WWII, yet we again see that boldness from Patek Philippe. I know that those readers who have or have seen a modern 5070 are already smiling, and that is the joy of going deep in this hobby!

Patek Philippe stopped the production of stand-alone chronograph wristwatches in the 1960s. For more than 30 years, the brand’s sole focus remained on the iconic perpetual calendar chronograph references: the 2499, which lived through four generations from 1950 to 1985, and the reference 3970 from 1985 onwards.

So, what was happening with A. Lange & Söhne all these years? Following WWII and the expropriation of A. Lange & Söhne by the Soviets, Walter Lange fled to Pforzheim in 1948. As mentioned above, only a few wristwatches were produced during the 1940s, along with the caliber 28, by the hands of Walter Lange. The successor tried to revive the brand a couple of times in Pforzheim, alas, to no avail. He also visited Glashütte and kept connections there, but the time just didn’t come. Therefore, we cannot actually speak of A. Lange & Söhne from 1948 to 1990.

The return, however, was something to talk about.

One of the last Lange wristwatches. Still very well made, with a few inward angles on the movement, and delicate finish. Thanks to my good friend, Z.

Patek Philippe v A. Lange & Söhne - The Modern Chronographs

For the sake of accurate and non-confusing comparison, this part of the article is going to follow a contextual timeline rather than a chronological one.

First part is going to be the comparison of basic chronographs and movements:

- Datograph v Patek 5070

- 1815 Chronograph v Patek 5170 & 5172

- L951.6 v CH 29-535

The second part is going to be the comparison of the Split-Seconds pieces and movements:

- A. Lange & Söhne Double Split v Patek Philippe 5959 – Movements

- A look at overall design and finish

- A. Lange & Söhne 1815 Rattrapante v Patek Philippe 5370 – Movements

The quartz crisis brought the mechanical watch industry to its knees. The advancement of quartz destroyed the fundamental value offered by the Swiss Precision Watchmaking Industry, and the brands had two choices: Either be extremely bold and position yourself above just “timing” instruments, or walk along the new reality, get sold and perhaps wait for the industry to recover, if it does.

Swiss’ response to the new reality was the quartz movement Beta 21, produced by a consortium formed by 20 Swiss Watchmakers, one of them being IWC. A watchmaking powerhouse back then, IWC already had an impressive portfolio, and despite adapting to the quartz movement with Beta-21, the famous Ingenieur came in 1976, the company was for sale. In 1978 IWC partnered with Porsche Design – and this attracted some important eyes. VDO, the tachometer producer also for Porsche, then took over IWC in the same year, along with Jaeger LeCoultre as part of a different deal.

Who would manage such names? One who knows about watches, knows the German Management, and understands the French? Well, that was Günter Blümlein. With Walter Lange’s words: A full-bloodied entrepreneur, incredible hard-working man and a marketing genius.

Blümlein put IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre back on track with a focused portfolio for each brand and emphasis on branding. Perhaps, it was time for new opportunities.

From here on, I am quoting from Elizabeth Doerr’s fantastic article over at quillandpad.com:

“The next important step came when the Berlin Wall fell,” Pantli reminisced. “Keck (CEO of VDO), Blümlein, and I were at a restaurant when we heard on the radio that the Wall had fallen. Because I had already been to see the Langes in 1976, I said, ‘This would be the moment.’ The two just looked at each other . . . in A. Lange & Söhne’s ten-year anniversary publication it was nice of Blümlein to write that I had had the idea because anyone could have had it afterwards. Two weeks later, we were in Glashütte to look around and see what could be done.”

Not long after, when the negotiations were done with GUB and when Blümlein called Walter Lange if he would like to revive the brand once again. A. Lange & Söhne was born in December 7th 1990.

I’ll now fast-forward to 1998. If you’d like to learn the rest of A. Lange & Söhne’s story, please have a read here: The Definitive Guide to Lange 1. From this moment on, the article is going to take quite the technical turn.

Patek Philippe v A. Lange & Söhne - The Basic Chronographs

Things do not happen in a vacuum. Patek Philippe, already at the very top of watchmaking, recognized something. For the first time in about a hundred years, competition was brewing across the border. A. Lange & Söhne made quite the statement in 1994 with the likes of Lange 1 and Tourbillon Pour le Mérite, and it was obvious the rest would follow.

In 1998, something unexpected happened: The chronograph for Patek Philippe was back after 30 years! In a 42 mm package, and with one of the most unexpected designs you would ever see. The reference 5070.

Only the next year, A. Lange & Söhne dropped the mic. If I may be so reserved, I’m going to say: The Datograph, introduced in 1999, re-defined its genre.

The similarities between these two watches are:

- They are both chronograph watches

- They are made of metal

And it ends there. How delightful to have such two characteristic pieces to write about!

First, let’s have a look at the case designs. Even from the front, the difference is obvious as French vs. German. On Patek Philippe bezel, you see several layers, so-called the double bezel to accommodate the 42 mm case. Remember, the 2512 featured above was 46 mm, so Patek was in-fact reserved for the 5070 – but still, well above the size trend of 1998.

Datograph on the other hand is one solid piece of metal, with a domed bezel sloping through the mid-band as one. We are going to see more details, but this is just Lange’s teutonic language, striking through every detail.

The side profile reveals even more. Look at the overall structure. Patek Philippe’s 5070 is svelte, gracefully expanding and narrowing towards the case back with a continuous flow. A. Lange & Söhne’s Datograph on the other hand is like a bodybuilder. It is built, sharply sculpted. You can easily observe the layers, without any additional curve or notches. The Datograph’s case back is protruding, housing the immaculate L951.1, whereas the Patek’s 5070 is flat at the base and expanding step by step rather than one big jump.

The lugs of the 5070 softly merges with the case, whereas the Datograph’s lugs are notched at the base. Patek Philippe gave extra linings to the thin lugs but kept the rounded profile. A. Lange & Söhne again opts for sharp transitions, from the top of the lugs to the bottom you see a triangle, merging at the base. Also, Patek Philippe’s 5070 is fully polished, emphasizing the flow even more, Datograph on the other hand is brushed in the middle, creating an industrial contrast. As if you’d think the cases are made by Thyssen & Krupp.

To give you measurements: Patek Philippe 5070 is at 42 x 11.6 mm and the A. Lange & Söhne Datograph is at 39 x 12.8 mm. When you feel both on the wrist, all I can say is, Datograph is just a tank compared to 5070. It’s heavy and much more present despite its more modest size. A nod to the pocket watch days.

On the dials, it’s obvious once again that these two legends are representatives of two completely distinct approaches. One basic difference is though, one is constrained due to its movement, and the other one is liberated because of it.

The 5070 utilizes the Lemania base, conceived for watches that are much smaller. When Patek Philippe decided to grow the 5070 to 42 mm, the chronograph registers had to come closer to each other. Imagine, the same movement is also present in Breguet 3237, and that watch is only 36 mm! With such proximity, the rest of the dial would be empty. There comes Patek Philippe’s brilliant design to oversize sub-dials, add tachymeter and an outer second track, continued by the double bezel. The relaxed font and darkened numerals add more to its soul, and the 5070 comes out as a wonder, becoming even more charming for its “shortcomings”.

Datograph, on the other hand, just like its case, is a geometrical delight. It is built as a whole, without any restriction, so A. Lange & Söhne could paint as freely as it wanted. The result was a one-of-a-kind gem that differs from all the chronographs produced since its invention.

The big date is of course the most striking element here. It forms a perfect triangle with the lowered sub-dials. Then, the Roman Numerals complement this triangle. The tachymeter sits on a raised plane, adding further depth to the dial.

The 5070P (left) and Datograph (right). Courtesy of The 1916 Company, Perpetually Patek Podcast.

These two approaches are going to be present in all the watches we are going to discuss below. Patek Philippe is going to focus on more Swiss, slender, thinner designs, whereas Lange is going to be heavier, broader, more geometrical, if I may say so.

Now, let’s flip these over. You’ll know when you see it, so I won’t elaborate further. I think for the seeing eyes, I do not have to. But ı will save that comparison between Patek Philippe’s CH29-535 and L951.5 for later.

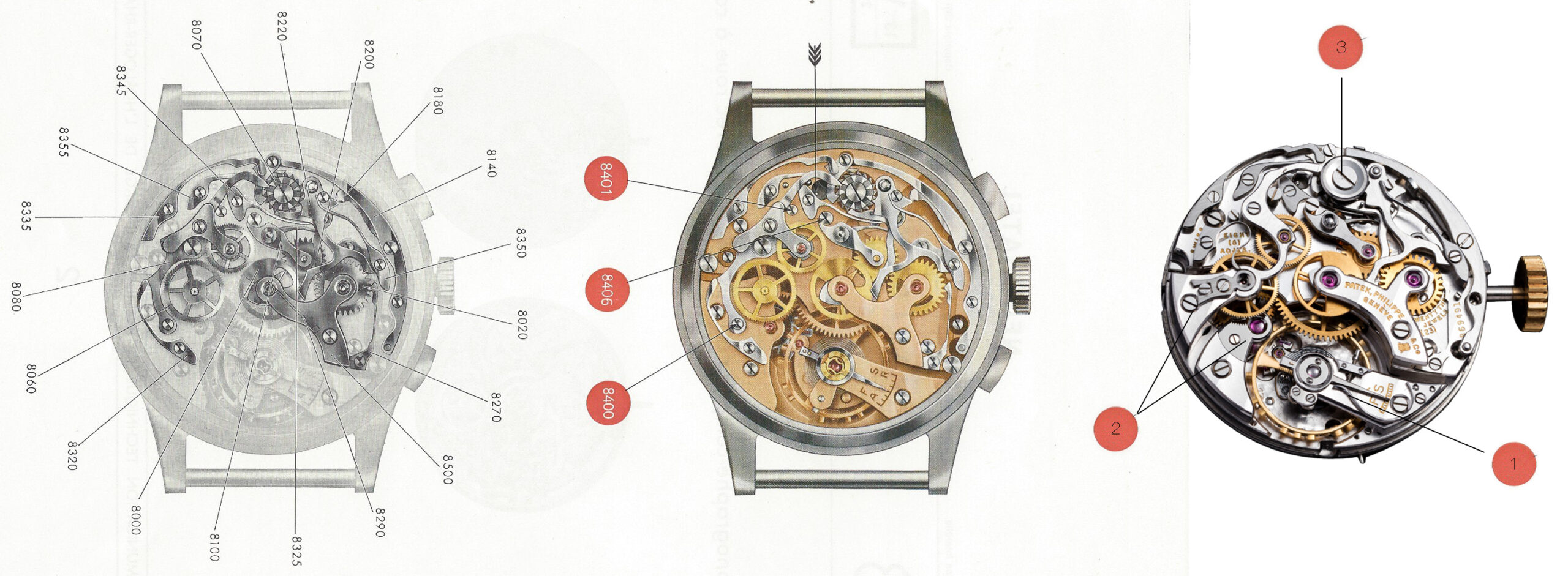

Patek Philippe’s Lemania based chronograph (left) and A. Lange & Söhne Datograph’s legendary movement L951 on the right. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The 27 mm re-worked Lemania caliber sits a bit too small inside Patek Philippe 5070’s rather assertive case. The finishing is top-notch, surely the best among the brands which utilized Lemania for decades, and one might argue that it’s even better than the modern in-house caliber of the brand. The movement, made of brass, has every part finished carefully, appearing mostly monochromatic in tone. There are angles given to levers to improve aesthetics, but I think it falls a little short. I can say, Patek Philippe extensively re-worked the base caliber to its exacting standards.

One thing, however: the Datograph would redefine those standards.

Datograph’s L951.1 is simply iconic. To this date, I’ve yet to see a more beautiful construction & finish of a manually wound chronograph movement. The base plate and bridges are made of German Silver, bringing a fantastic harmony with the gold chatons, blued screws, flat polished active parts and red jewels. The intricacies of the chronograph movement are incredibly well showcased, with each part finished according to its function – i.e., static parts are flat polished to a mirror-like effect, while active parts are straight grained. Every three screws hold a chaton around a jewel. The inward angles on the bridges, as well as the hand-engraving on the balance cock, complete the picture,

It just leaves you wondering if any better will ever arrive.

Patek Philippe’s 27-70 is a classic chronograph with a dragging minute hand and no flyback function. It was normal and good for its time, up until the arrival of A. Lange & Söhne’s Caliber L951.1. The latter comes with a flyback function, as well as a jumping minute counter. In 1999, because of a once-defunct, East-German luxury watch manufacturer – oh the irony – almost all other chronograph movements suddenly seemed archaic. On the bright side, it pushed the Swiss Watch Industry to reconsider the outsourcing system and forced their hand to come up with proprietary chronograph movements.

You know, James Joyce says:“Three things are needed for beauty: wholeness, harmony, and radiance.”I think the 5070 misses the wholeness but exudes radiance much greater than what it loses. With the Datograph, however, the trio is complete.

A. Lange & Söhne went from antiquity to absolute superiority with the Datograph. No early design or movement to rely on, just a rather small brand, coming out with the best there is. This success story was what hooked me to the brand almost 15 years ago.

Intricacies. From A. Lange Story Episode 3

CH 27-70 from Patek Philippe. From Perpetually Patek

Patek Philippe 5170 & 5172 v A. Lange & Söhne 1815 Chronograph

Following the Datograph, A. Lange & Söhne did not stop. The Datograph was (and is) already an icon, but with its heft and added big date, it was a bit challenging for some in the segment. In 2004, Lange introduced the 1815 Chronograph. The same beating heart but stripped down from the big date and Roman Numerals, it turned to a more classical façade. From Black Sabbath to Ozzy Osbourne, perhaps?

Patek Philippe, on the other hand, continued with the production of the 5070 in different metals and dial combinations. It was in 2009 that Patek Philippe launched its first in-house basic chronograph movement, caliber CH 29-535 PS. The references we’re going to look at are the 5170 & 5172 vs. the 1815 Chronograph.

Patek Philippe’s 5170 measures 39.4 x 10.9 mm against the 1815 Chronograph’s 39 x 10.8 mm. Very similar in size, it’s again the case flare that differentiates them. Thanks to the in-house movement that fits its case, the 5170’s bezel slopes in one step as opposed to 5070’s stepped bezel, and merges with the middle case. Here (top case in the figure above), you can see the very thin arrangement on all layers, delivering a slenderer look than the actual measurements suggest. The lugs flow with the case as one piece, further emphasizing the thin block. Patek Philippe’s modernization of the 5070’s case is a masterpiece, and something we’re going to talk about a lot in the coming sections.

The 1815 Chronograph, on the other hand, retains the signature elements mentioned in the 5070 vs. Datograph section, this time with a thinner bezel and case back. You might notice that with the 1815 Chronograph, the crown sits right in the middle case as opposed to the Datograph. That’s because of the removed big-date mechanism, which occupies about 2 mm at the top plate.

As for dial design, we have plenty of references to talk about and choose from. The 1815 Chronograph of Lange and 5170 & 5172 of Patek Philippe are very rich, individual collections. There’s something for everyone.

Delights! From the archives of The 1916 Company. Some sold at Langepedia Marketplace.

In the above figure, you see a summary of modern Patek Philippe and A. Lange & Söhne’s chronographs – in chronological order from left to right. Observe that Patek Philippe started with Roman Numerals and a pulsometer with the 5170J, drawing inspiration from mid-century chronographs. Then with the 5170G, the brand opts for applied Breguet Numerals, later also removing the pulsometer for a cleaner, more modernized appearance.

What happens next is interesting – the 5170P appears with baguette diamond indexes and a sunburst dark blue dial. It’s a tremendous twist on the classic chronograph design, one you’d expect from Patek Philippe’s bold design heritage. It might take time to get used to, yet the character and uniqueness of the piece transcend any tradition. It modernizes and shifts the collection to a more daring, sportier look.

This evolution opens to the current 5172, which Brian Govberg defines as a “nouvelle vintage” watch from Patek Philippe. At 41 mm, with syringe hands, a delightfully sporty font filled with lume, and an incredibly well-made stepped case, it’s almost a sports watch, and just damn good looking!

As Patek Philippe draws inspiration from mid-century chronographs, A. Lange & Söhne looks to the pocket watch heyday with the 1815 Chronograph. The collection starts with a broad pulsometer design, two-tone and multi-layered dials. In 2010, it evolves with the removal of the pulsometer and enhanced sub-dial size for a cleaner look. In 2015, with the introduction of the third generation, the collection merges the best of both worlds, featuring both the pulsometer and the optimized sub-dials.

What I am missing is though, that courageous touch. Why not one small run with say, with a stone dial, perhaps a Roman Numeral? There was a mother of pearl dial 1815 Chronograph, though rather loudly made, I am sure if wanted, A. Lange & Söhne could stir the pot just like Patek Philippe has done with the 5170P. Oh well, I do hope that we witness it.

The 1815 Chronograph Darth. Sold at Langepedia Marketplace.

Patek Philippe 5170G. Courtesy of Hodinkee

Once again, we see Patek opt for simpler, slimmer, and cleaner looks with rather flat dials and cases, whereas Lange gravitates towards a multi-layered approach with each element sitting on its own level, creating a depth that can only be matched by its brilliant movement.

Lange follows a traditional line, offering hallmarks from the pocket watch days such as printed Arabic numerals, railway minute tracks, and the same style of case & hands, only adding small nuances here and there. It’s a tremendous piece for those looking towards classics, but with a twist such as lowered sub-dials and, specific to the 1815 Chronograph Boutique Edition, dark blue indices.

It ultimately comes down to taste, and I’m not going to deliver an in-depth review on the design of both collections. What I’m trying to convey here is Patek Philippe’s more daring approach to design and willingness to evolve, compared to A. Lange & Söhne’s stronger footing in history and reluctance to step away from that circle. This difference will become even more evident when we start to talk about more complicated pieces.

Flipping these gems over, this time, Patek Philippe greets us with something new.

Patek Philippe CH 29-535 vs A. Lange & Söhne L951

In the introduction for the 5070 and Datograph section, I didn’t delve much into technical details. This was because, as modified as it was, the 5070’s movement was based on Lemania, while the Datograph was indeed above and beyond in terms of both technicality and aesthetics. But now, with Patek Philippe’s in-house movement, a proper technical showdown awaits us.

However before that, I would like to give a bit context.

A. Lange & Söhne introduced the Datograph in 1999 in BaselWorld fair, within a shared booth with IWC. For those who visited fairs for a long time would know that Lange brings a giant model of each year’s highlight piece. In 1999, that highlight piece was just the 30:1 movement of the Datograph. Not the whole watch, just the movement. It was, indeed, that impactful in the industry.

Everybody in the fair would look at that movement with awe, congratulating Blümlein, Reinhard Meis and Walter Lange on such achievement. However, there is one select name who stood there, looking at it for minutes. Philipp Stern of Patek Philippe.

There was a lot going on in the 1999. Swatch Group acquired Breguet, hence Lemania (the movement supplier for the 5070), Richemont was starting to come up, etc.. But in addition to all this, the Datograph’s effect was tremendous. So much that, Patek Philippe came out with an in-house chronograph only a few years after. A concrete example of how l951 re-defined the standards, and opened up a new path in watchmaking.

Now, let’s have a look at each of them.

Once again, we see the contrast between Genevan and German watchmaking. As I went through the aesthetics of Lange’s L951 earlier, let’s focus on Patek Philippe’s Chronograph. We see a structure made of multiple bridges, with Geneva stripes over brass bridges, flat polish over the column-wheel cap, and straight graining over the functional steel parts. We also see that the bridges and levers have more curvature to improve aesthetics, and rather than providing depth, the whole movement sits on a rather equal surface.

However, the new caliber falls short of the earlier Lemania-based movement in terms of overall finishing. The anglage is visibly thinner, and we don’t see delightful inward angle(s). The new caliber feels too rounded, rather than displaying the necessary handwork to give it sharpness. It is indeed very nice, and in a world where the L951 didn’t exist, it would be a top contender perhaps. Alas, to my eyes, it’s not nearly as aesthetically pleasing as its German counterpart where delightful elements and colors are plentiful. I can even claim that a Montblanc Pulsograph with Minerva at $33k (in 2020) has much better finishing than Patek Philippe’s modern chronograph.

Though, it is not all finishing, is it?

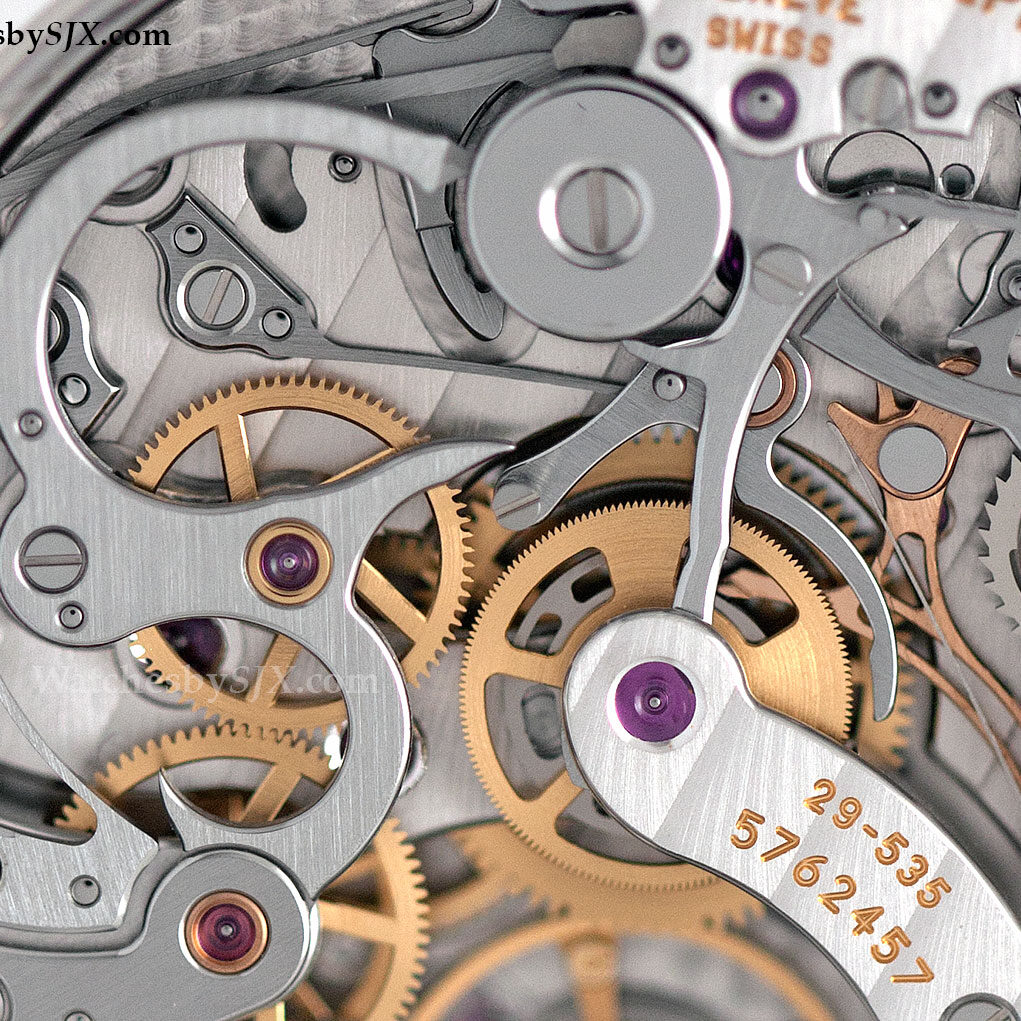

CH 27-70 (far left), the new CH 29-535 (middle) and L951.

Where Patek Philippe excels is technicality.

In the Great Lange Debate, sparked by the great Walt Odets in 1999 upon the introduction of the Datograph, Mr. Odets complains about the “lack of innovation” within Datograph’s L951. I went extensively detailed in my “The Collector’s Guide to Datograph” article, but to give a small summary he explains that the jumping minute counter, as well as flyback are features that can be found also in mid-century watches. Hence, there is no technical innovation in this “new” caliber.

Indeed, Mr. Odets has a point. As Reinhard Meis, the technical director at the time, also confirms, the Datograph is an utterly traditional movement, combining the best of its time both aesthetically and technically, but does not advance the latter. It’s just a damn good chronograph with a column wheel, horizontal clutch, buttery smooth pushers, and unrivaled looks.

Patek Philippe, on the other hand, takes a different approach.

Well, it had to.

The CH 29-535 is a technically very well-made and advanced chronograph mechanism. What it lacks aesthetically, it makes up for in engineering. It boasts six patents, and they are important both for longevity and efficiency. The optimized teeth profiling reduces friction and flutter of the hand. The arrangement between the clutch and blocking lever is liberated from the column-wheel, which enables finer adjustment and prevents wear of parts. Furthermore, the new caliber utilizes a jumping minute counter, just like the Datograph has been utilizing since 1999. The difference is, Patek Philippe does it with a specially arranged gear and a coiled spring as opposed to the traditional approach of a snail cam and lever.

To this date, not sure if there is a more beautiful chronograph.

The rather more modern, and optimized Patek. Courtesy of SJXwatches

These technical innovations in Patek Philippe’s movement are not just for show; they translate into tangible performance benefits.. Patek Philippe’s CH 29-535 offers 65 hours of power reserve and beats at 4Hz. Yet, for some reason, it lacks a flyback function. Whereas the first generation L951.1 beats at 2.5Hz with 36 hours of power reserve and offers a flyback. In 2010, however, A. Lange & Söhne unveiled the second generation fitted inside the 1815 Chronograph, now also with 60 hours of power reserve.

In short, I can say that Patek Philippe’s modern chronograph caliber is technically more advanced, not in terms of benefiting the user with functions such as flyback, but due to its longevity, efficiency, and serviceability. Whereas A. Lange & Söhne’s chronograph movement is more on the traditional side, but with exquisite and better handcraft and visuality, plus a very important flyback function.

One important detail: in 2015, the launch price of the 5170G was $75k, whereas the same year A. Lange & Söhne unveiled the 1815 Chronograph Boutique Edition at only $51k. I’ve long said that the 1815 Chronograph was the best buy in high-end watchmaking. Just unbeatable value for a long time.

In 2024, the 5172 sits at $83k and the 1815 Chronograph at $78k.

Despite the price hike, I still think that the 1815 Chronograph is a much better choice in terms of watchmaking. The looks? That’s up to you.

Now, we pull out the big guns.

Patek Philippe v A. Lange & Söhne - Rattrapante

I believe one very much underappreciated aspect of constructing complications is the dexterity to thin them. Recall the repeaters made by AP during the 1920s, measuring as small as 15 mm in diameter and just coin-thin. Or the split-seconds calibers made by Victorin Piguet, at just 6 mm thickness… Incredible, incredible achievements. Today, we rarely see movements made to such high standards, and I’m afraid many are led to accept that multiple complications in a wristwatch measuring 20 mm in thickness (depends on the context, of course) is okay.

Well, miniaturizing a complication is as demanding as improving it, and here we have the two exact ends of the spectrum to start with. Each is best in its own merit, and both are superbly exciting!

Following the revival of chronograph collections in 1998 and 1999 respectively, the logical next step for both brands was to take it to the next level: The split-seconds chronographs.

As usual on the chronograph front, A. Lange & Söhne was the first to light the candle with the Double Split in 2004. Patek Philippe joined the party with the reference 5959 in 2005. Please note, these two watches play completely different tunes, but it’s important to give them a stage to understand the timeline and each brand’s strengths.

The venerable Double Split and graceful Patek Philippe 5959.

Looking at the dials, we see two completely different schools of thought. A. Lange & Söhne builds over the masculine Datograph with a panda look, preserving the Roman Numerals, and boosting it with the XII, with an additional power reserve indication where the big date previously sat. The hands are broad and lumed, further emphasizing the modernity and the “racing” spirit of the complication. Measuring at 43.2 x 15.3 mm, with classic Lange case construction, it reminds me of the Teutonic Knights in AoE2, heavy and engineered.

Patek Philippe’s 5959, on the other hand, is the definition of grace. The classic Breguet Numerals, accompanied by thin hands and simple font. Measuring only at 33 x 8.45 mm, with classic lugs flowing through the case. The design is almost an exact copy of the first split-seconds wristwatch with Victorin Piguet ebauche from 1923.

Brutalism vs minimalism. Two completely different styles, packed with two completely different, handcrafted mechanisms. Oh, are we spoiled!

Two exact opposites. The thinnest split-seconds caliber of its time (left) and an engineering marvel, and almost double in size (right).

You might have read or asked yourself one of the oldest questions about A. Lange & Söhne and Patek Philippe: who makes the best movements, or who finishes their watches better?

In the previous chapter, I believe the answer was rather clear between Patek Philippe’s 5070 – 5170 – 5172 vs A. Lange & Söhne’s 1815 Chronograph and Datograph. Even though it’s a topic for a different article, if we look at the basic 1815s, Lange 1s, etc. vs. Calatravas, etc., we would see that A. Lange & Söhne is the one going that extra mile.

However, when it comes to the echelon of watchmaking – the rattrapantes, the repeaters – unlike most, I would claim that the gap is closing, and I would argue that Patek Philippe even has an edge.

Look at Patek Philippe’s CHR 27-525 here. Its finesse is truly unmatched. There’s an incredible dance between colors and finishing techniques, with polishing and wide anglage given to the thinnest levers, curved with inward angles. While it’s based on a Victorin Piguet ebauche, the handcraft here is undeniable. Turn your head to the Double Split’s L001.1. It’s as intimidating and present as its case and dial. You see thick levers, built layer upon layer with an unparalleled depth and finished to perfection. An array of colors is given by the hue of German Silver, the gold chatons, and polishing.

Once again, two different approaches, and equally charming outcomes for different folks.

While Patek Philippe represents the thinness and grace end of the spectrum, A. Lange & Söhne represents the innovation and over-engineering side.

A usual rattrapante mechanism measures two events concurrently or comparatively. The operation is rather simple. With a push to the start button, the two stacked seconds hands start to move together. When the rattrapante pusher is pressed, one of the hands stops while the other continues. Eventually, you synchronize both hands, stop them, and return them to zero, thus allowing you to time two different events. However, despite having two seconds counters, rattrapantes typically feature only one minute counter. Well, at least until the Double Split arrived on the scene.

A. Lange & Söhne’s Double Split houses an additional minute counter. While both hands are running, when you press on the rattrapante hand, the hands split, and when the full minute is reached, the minute counter splits too, allowing you to measure both events up to 30 minutes, independently.

The Double Split also features an isolator mechanism that separates the rattrapante hand from the chronograph hand to ensure smooth operation. The caliber L001.1 further boasts flyback and jumping minute counter mechanisms. In short, it’s an incredible technical achievement in modern watchmaking, and even more so in 2004. Talk about over engineering. Well, that’s A. Lange & Söhne’s trademark.

All this complexity, however, comes at a cost. And that cost is wearability. The Double Split’s impressive functionality results in a watch that’s considerably thicker than traditional rattrapantes. But here’s a thought-provoking question: if it’s the only one of its kind and we have nothing to compare it to, can we really call it thick for what it is? Perhaps it’s simply the necessary size for such groundbreaking functionality.

The caliber L001.1. Courtesy of Reddit ctzn_voyager.

A. Lange & Söhne utilized the caliber L001.1 exclusively in the Double Split, and further enhanced it with the Triple Split in 2018 by adding a split hours module. Patek Philippe, on the other hand, has housed the CHR 27-525 in a variety of references, mostly at the highest end of their catalogue. In my opinion, some of these are prime examples of modern watchmaking craft.

While these two exceptional gems showcase the pinnacle of each brand’s capabilities, they represent only a fraction and as said, are almost two opposites. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of how these two giants approach this complication, we need to examine their classic —yet still incredibly impressive—split-seconds chronographs.

Once again, Patek Philippe’s design variety is mind-boggling. Yes, significant inspiration comes from mid-century designs, but the modernization, the courage to enrich the catalogue, and the choice given to collectors are admirable. A. Lange & Söhne, as usual, is more reserved, relying on its pocket watch days with two registers sitting on a vertical axis.

Among the numerous references above, I believe the most appropriate comparison can be made between the Patek Philippe 5370 and A. Lange & Söhne’s 1815 Rattrapante. Examining these two watches will give us a great summary for the article, distilling the essence of both brands in how they fare in modern watchmaking.

Patek Philippe v A. Lange & Söhne - 5370 v 1815

If you were to ask me to name the two of the best watches that have emerged from Patek Philippe and A. Lange & Söhne in the last decade, I would without hesitation point to these two horological gems. Each, in its own right, is so masterfully crafted, housing the respective brand’s signature elements executed to the highest level.

Two schools of thoughts, two masterpieces. Courtesy of a good friend, R.

It’s not my intention to delve deeply into the aesthetics of these two pieces. I believe it’s clear by now how both brands approach their designs, and that aspect is entirely subjective. Instead, I’d like to emphasize the differentiating details which I think matter, and of course, give an exhaustive look at the movements.

The number one point for the Patek Philippe 5370, even above its gorgeous looks and movement, is its case. It’s a masterpiece.

A modern classic. Courtesy of Sotheby’s Watches.

Made of platinum and measuring 41 x 13.56 mm, it is an incredibly well sculpted piece of metal. The bezel makes a concave form and merges with the case band. We see the band expands just a little and is monobloc. Please observe how the mid case band is recessed and given a brush finish, brilliantly contrasting with the polished top and bottom case. The lugs flow through the mid-section, and crowned with cabachon, drawing inspiration from Patek Philippe’s mid-century chronographs.

The pushers are generously anglaged and given polish at the sides to create another layer of contrast against the brushed band. When you look at the overall structure, you see how much of a positive effect the design has on the thickness of the watch. The sculpture just hides the thickness, delivering that Patek Philippe flair.

The 1815 Rattrapante Honey Gold measures 41.2 x 12.6 mm. The stepped bezel adds that much-needed grace. This was a welcome addition to the brand’s cases, arriving with the second generation of the 1815 Up/Down in the mid-2010s. We further descend to enjoy the contrast of the brushed band and polished back ring. The lugs are notched at the base, as usual, making a strong distinction from the main case.

Just a few last words on design. Patek Philippe’s matte Breguet Numerals on black enamel with leaf hands is just breathtaking. Lovely, lovely combination, and I am rather sure that we are going to see this collection moving into the sportier direction, just like 5170 and 5172.

Lange finally brings that much needed excitement to its designs and utilizes the gilt look on the dial, coupled with the incredible hue of honey gold case. From the red-three dots on each 15 minutes, to “GLASHÜTTE IN SACHSEN” it has a soul that only a few Lange pieces can match, screaming that it is coming from the very depths of Glashütte Watchmaking. I hope to see such bold decisions more and more.

1815 Rattrapante Honey Gold. Courtesy of budgecoutts.

Now, let’s talk watchmaking.

The beating heart of the Patek Philippe 5370 is the caliber CHR 29-535, based on the simple chronograph caliber of the same name. It incorporates all the innovations from the basic caliber and improves further upon them, creating a proper 21st-century split-seconds chronograph mechanism. The new caliber also houses an isolator mechanism (familiar from the Double Split).

Furthermore, the CHR 29-535 is a truly traditional split-seconds mechanism with its crown-pusher, completing the whole package. It has an instantaneous minute counter, beats at a generous 4Hz, and offers 65 hours of power reserve.

5370p’s movement finish is miles above its base chronograph version. Courtesy of SJXwatches

A. Lange & Söhne’s 1815 Rattrapante, on the other hand, stays rather old-fashioned. From the construction to frosted finish, it’s almost a reincarnation of pocket watches from the 1900s. This extends to its technicality as well. The caliber L101.2 is modularly constructed, with layers upon layers. Hence, the balance is hidden beneath the second column-wheel. To achieve the desired thinness, the levers are flattened, yet still rather broad.

The caliber L101.2 operates with an extra pusher. It offers a semi-instantaneous minute counter, beats at 3Hz, and provides 58 hours of power reserve. It lacks the isolator mechanism and utilizes a spring to synchronize the chronograph and rattrapante hands. It’s rather interesting to see a wire spring in such a high-end movement at this price. Another example employing a wire spring for the same purpose is Habring’s genius Doppel, which costs around $12k.

1815 Rattrapante’s rather traditional and very special L101.2. Courtesy of budgecoutts

Mr. De Haas’ answer (via Hodinkee) to this is straightforward, stating that the isolator adds thickness, hence the brand opted for a simpler solution. This explains the 1 mm difference in thickness between Patek Philippe’s 5370 and A. Lange & Söhne’s 1815 Rattrapante. Please note that this is a very important detail.

For years, A. Lange & Söhne did not resist the urge to put out extremely complicated, engineering focused gems that earned the brand a cult following of movement manufacturé but on the flip side, most pieces appeared as hockey pucks due to the needed space as well as the case structure. Therefore, it is very refreshing and encouraging to see that when needed, Lange can indeed thin the movements and can be just as adept.

Finishing-wise, Patek Philippe takes the cake for me as well. Just as we saw in the Victorin Piguet based movement, observe how thin and elegant the levers and construction are. Yet, they’re still finished to perfection with straight graining on steel parts, polish on rather static parts, and generous anglage on every curve. Not to mention the myriads of sharp angles. It’s still a borderline thin movement for what it is, but still maintains great depth.

The 1815 Rattrapante is also meticulously finished, but the construction is lacking, even when compared to Datograph’s L951. It’s thin, and heavily sacrifices depth to achieve this. The hidden balance cock is a significant negative, as it’s one of the brand’s signature elements. Still, we see a myriad of sharp angles, flat polish, and anglage on the levers and bridges.

The trade-offs made by each brand come at a certain price, though. The Patek Philippe 5370P with blue enamel was introduced at $263k, whereas the 1815 Rattrapante Honey Gold would set you back about $134k. That’s a whopping difference – one that can be explained by differences in craft, watchmaking, technicality, and of course, branding. On price / watchmaking merit, I know my money goes to the 1815 Rattrapante.

Patek Philippe v A. Lange & Söhne Chronographs - Concluding Thoughts

Throughout this exploration of Patek Philippe and A. Lange & Söhne chronographs, we’ve delved into the intricacies of design, movement construction, and finishing techniques. We’ve seen how each brand approaches the art of chronograph-making, from basic models to split-seconds complications. Their distinct philosophies have become evident, reflecting not just different technical approaches, but also divergent interpretations of tradition and innovation. As we near the end of the article, it’s worth stepping back to digest it all.

If you allow me, I’d like to offer a few concluding thoughts on the matter of Patek Philippe vs. A. Lange & Söhne Chronographs.

The construction of a chronograph is a delicate work. Datograph’s movement enchanted me into watchmaking when I first saw it in 2010. I was amazed when, back in 2018 while visiting the manufacture, a great watchmaker working on the Tourbograph Perpetual offered me a seat at his bench, lent me his eyepiece, and allowed me to explore the movement as it was built. It was a religious experience for me, and to this day, I enjoy every aspect of talking about, examining, and writing on these gems.

A.Lange & Söhne sits in a camp of traditional and reserved design with rather long product cycles. Understandably so, as the volume is significantly lower than Patek Philippe. For example, each Datograph generation has spanned more than a decade, and the third generation of the 1815 Chronograph is approaching a decade. Patek Philippe, on the other hand, with its rich heritage, offers many more choices and more daring designs that could be future classics. This is a very strong selling point for Patek Philippe, as a significant percentage of buyers remain confident that the brand will discontinue pieces in a few years.

The Datograph “25th year” special edition in white gold with blue dial.

The evolution within the 5170 and transition to 5172 is evident that Patek Philippe still wants to lead the way.

A. Lange & Söhne relies on a proven case design that is industrial, defined, and geometric. Patek Philippe’s cases are graceful, slender, and elegant, focusing on rounded profiles. However, these are design choices, and I’ll leave it up to you to decide your preference.

I believe we can argue that A. Lange & Söhne offers a much more complete package up to a certain point, e.g., basic chronographs, and indeed great value (in terms of watchmaking) against Patek Philippe with its craft. Patek Philippe’s caliber CH 29-535 is newer, indeed more modern, but lacking in handcraft and important properties such as flyback compared to A. Lange & Söhne’s L951.

When we move to split-seconds chronographs, this is where we see Patek Philippe shine. The CHR 27-525 is an exception, but even if we look at the more streamlined CHR 29-535, we see drastic improvement over the basic version in terms of handcraft and architecture. There is a significant price difference at this range, and it’s up to you to decide how much you value each brand or each aspect of watchmaking.

A. Lange & Söhne inspired a whole industry for in-house movements, indirectly encouraged many coming independent watchmakers to come up with their own, and Patek Philippe learnt from that. Patek strived to be better, in certain aspects, still with a strong focus on design and wearability.

In return, Lange can learn from Patek Philippe too! Perhaps a bit more focus on cases, a bit more variety and courage on the design. The competition makes it better.

Outlook, Competition, Further Read

2024 marks the 25th year of A. Lange & Söhne’s legendary caliber L951.1. Developing a brand-new calibre is a demanding investment, and I believe this gem still punches above its weight. Lange updated the movement back in 2010 with an extended power reserve, and I expect we’ll see a similar approach in the coming years, where needed.

On the design front, we’ve had the Datograph Up/Down since 2012, and the 1815 Chronograph’s third generation since 2015. It’s time for a new generation of both, and I’m looking forward to what’s next. It’s clear that while the Datograph is moving towards a sportier appearance, the 1815 Chronograph will likely keep one foot in tradition. I can only hope for a thinner and an updated Datograph. Lange has the means, the talent and perserverance, so I am keeping my hopes up!

The 1815 Rattrapante is also quite versatile, and I predict we’ll see a few new iterations. Lange’s Double and Triple Splits are game changers, but their thickness limits their market appeal. As Lange seems to be focusing more on high complications, I hope we’ll see watches with better wearability.

Patek Philippe, on the other hand, is newer to the chronograph game, but more technically advanced. The brand already offers two split-seconds and one basic chronograph movement. Improvement for Patek Philippe could focus on the latter, especially in its finishing. As for the split-seconds, they’re nearly perfect as they are.

We can see Patek Philippe moving in a sportier direction. Not mentioned here, but if you look at the 5470P or 5373P, it’s evident that the brand wants to keep on track with the 5172 and expand in that direction – a move I highly welcome.

Looking at the competition, we see only a few contenders (among big brands) in various styles and price points. Vacheron Constantin’s Harmony Split-Seconds Chronograph comes to mind – one of the most impressive watches of the last decade. With its peripheral rotor, incredible finish, and thinness, it reminds you why Vacheron is, well, Vacheron.

Broadening the horizon, Audemars Piguet deserves a strong mention with itsLaptimer, an incredible feat of chronograph wizardry that I think is severely underrated or simply unknown.

From the independents, of course Petermann Bedat with an exceptional split-seconds shines. Albeit based on Valjoux 13, extensively improved and just perfected – for a price. MB&F’s Sequential Evo is another gem that sparks a huge interest for the technical mind.

For the base chronographs, as mentioned Habring’s Doppel offers an incredible value for anyone. Going a bit upwards, we see Grönograaf from Grönefeld Brothers. Just a fantastic movement, retaining the brand’s signature flipper from 1941 Remontoire.

I hope this has been a valuable guide for enthusiasts looking to understand the nuances between A. Lange & Söhne and Patek Philippe, the strengths and weaknesses of each brand, and to help with your decision-making process.

Please don’t hesitate to contact me via alp@langepedia.com with your views on the article, suggestions, or simply to chat!

Thank you for your time.

Further Read

Please feel free to contact:

Follow Langepedia on Instagram:

Watch “A. Lange Story” Documentary, in partnership with WatchBox:

STAY IN TOUCH

Sign up for the newsletter to get to know first about rare pieces at Marketplace and in-depth articles added to the encyclopedia, for you to make the most informed choice, and first access!